Dog days, dog stars and flea peppers

Plus: Empty Lots in paperback and a nature writing class. (No. 183)

Early Tuesday morning, around 5:30 a.m., I heard someone hollering down in the woods. It was super dark, the waning crescent moon low in the eastern sky with Jupiter, Venus, Castor and Pollux. The noise sounded like it was coming from the municipal wildlife sanctuary under the bridge, about a half-mile away. A few years ago you would have been more likely to hear coyotes calling from there, or owls, but since lockdown the parks and woodlands along the river and creeks here at the eastern edge of town have all become more frequently and densely occupied by dislocated members of our own species. The newest camps have motor vehicles, generators, dogs, and ingenious structures made from found materials, and when you stumble upon one of these improvised communities while out for a walk in the August heat you can’t help but think that what once felt like signs of the precarity of life under 21st century American capitalism now feels more like a slow-motion collapse.

Many of our newest neighbors relocated here after the floods forced emergency evacuations of other camps. The floods weren’t as bad in Austin as they were in the Hill Country, since we are protected by the series of Depression-era dams upriver. We got the water though, the farthest it’s been above its normal banks in a decade, and when it receded a couple days later the woods were filled with flotsam, mostly our trash. When I came upon this mushroom of a type I’d never noticed before, I found myself wondering if it might be some rhizomatic expression of the tens of thousands of fragments of styrofoam that surrounded it on the forest floor.

July’s floods followed a tremendously damaging windstorm at the end of May—a microburst with 85 mph gusts that uprooted the 80-year-old mesquite in our yard and two huge cottonwoods that had grown more than a hundred feet tall around the mouth of a city drainage pipe that empties into the floodplain behind our house. That storm followed three years of extreme temperatures—historically anomalous deep freezes and winter storms one never used to have here, two of the hottest summers on record, and a long decade of drought. The woods have suddenly become a graveyard of fallen giants, and I wonder how they will evolve with these new holes in the canopy. The invasive Johnson and Bermuda grasses that dominate the upland terraces need full sun, and so the shade of those big trees created a zone where the inland sea oats and wild ryes could carpet the forest floor every spring and bring more biodiversity with them.

This is mostly a young forest here along the banks of the Colorado in East Austin, the majority of trees having grown in the past five decades since gravel dredging and other industrial activity was pushed further east. It took me a while exploring the area to realize it was not the miraculously intact remnant I had assumed, but something even more wondrous—a stretch of riparian land that had rewilded on its own after being left alone by us, in a brief historical moment when it managed to hide in plain sight.

Such wonders, alas, never seem to last.

You can really feel the development pressure amping up along the edges of this corridor, with an undercurrent of brutality I didn’t foresee. The deserted traffic island I’ve frequently reported on here, which for a time was home to a nested pair of red-shouldered hawks I once spotted mating in one of the ancient pecans that grew in that unlikely arbor between two onramps, has been filled with an apartment block that looks more like a border wall than a work of architecture (notwithstanding the developer’s naming the project “The Eclectic”). The big dig that will channel all the water that drains off expanded Interstate 35 to a pump station next to one of those onramps is now underway in earnest, big machines working at night to open up giant holes in the earth for the underground boring machines to tunnel their way here from the entry point being walled off at what’s also the entry point to downtown.

Our local government, despite its pretenses of progressivism, seems completely captured by real estate capital and devoid of any real concern for affordability, environment, or diversity. And then you read the headlines out of Washington, a daily barrage of weirdly performative policy reversals that lead one to think it’s not so much that they don’t believe our burning of the world is overheating it to the point of mass extinction, but rather that they get turned on by the idea, like some insane death cult that gets off on the power of bringing about the end and making dark fortunes in the process. Daring us to step away from our work stations long enough to organize and take the collective action that should be so easy but seems so paralyzed. Even as we can all remember five years ago, when that same freeway was shut down by a flash mob of incensed protesters, and we got a glimpse of the power the multitude could yield if it could sustain it for more than a microburst.

It’s not all bad. While the growth booster part of the city greenlights all the crappy projects, another contingent works hard to add new public lands, with an emphasis on lands along the river corridor, despite ever-increasing efforts of the state legislature to strip the local governments of any regulatory power. Our municipal water stewards have intervened to control and clean the outflows from TxDot’s insane I-35 drainage project. And everywhere you look, you can signs of life and evidence of ecological resilience. The old man’s beard that blooms in the hottest pockets of summer, tiger swallowtails mating in the shadows still cast by the trees that fell, whistling ducks that come and go at dawn and dusk between the river and their roosts behind the old industrial lots. We had good rains all through June and July, and the flora and fauna show it.

The most heartening sign for me in the past two weeks has been the early arrival of abundant fruitings of chiltepin. The ur-pepper of the Americas, it can only germinate after passing through the digestive system of a bird. When it does, it grows as a shrub, usually in shady spots, a scruffy little plant with tiny white flowers that might easily escape your notice until the flowers turn into peppers and the peppers ripen from green to red and tempt you to taste the burn hotter than a habanero. A plant that only grows in the places that don’t get mowed, and the one from which the botanists think all the other peppers on our table were derived. An ephemeral being that is also one of the oldest living things around, and a window into the wilder world we came from that still expresses in the margins of our dominion.

Today I hope to make some hot vinegar with a sampling from the bushes in our yard, and start the work of tending our pocket prairie for the winter growing season that incubates spring. We’re lucky to have refuge, and daily reminders that what sometimes feels like the end can also be an opportunity for new beginnings.

Thursday evening I found a downed bird nest by our front door, blown by that afternoon’s storm from its mooring in the mustang vine that hangs from our green roof. The fledgling cardinals recently reared there had already flown off, so no active home was lost, and we could admire the nest’s Anthropocene construction: fragments of clear plastic packaging harvested from the industrial yards around us woven in to better insulate the beautifully threaded coils of dried native grasses. All the cardinal nests are like this, every season, reflecting a learned adaptation to the world we’ve made and an intelligence we don’t really understand. Evidence of the weird new nature cyborg nature aborning, it makes me mildly horrified and modestly hopeful about what’s to come.

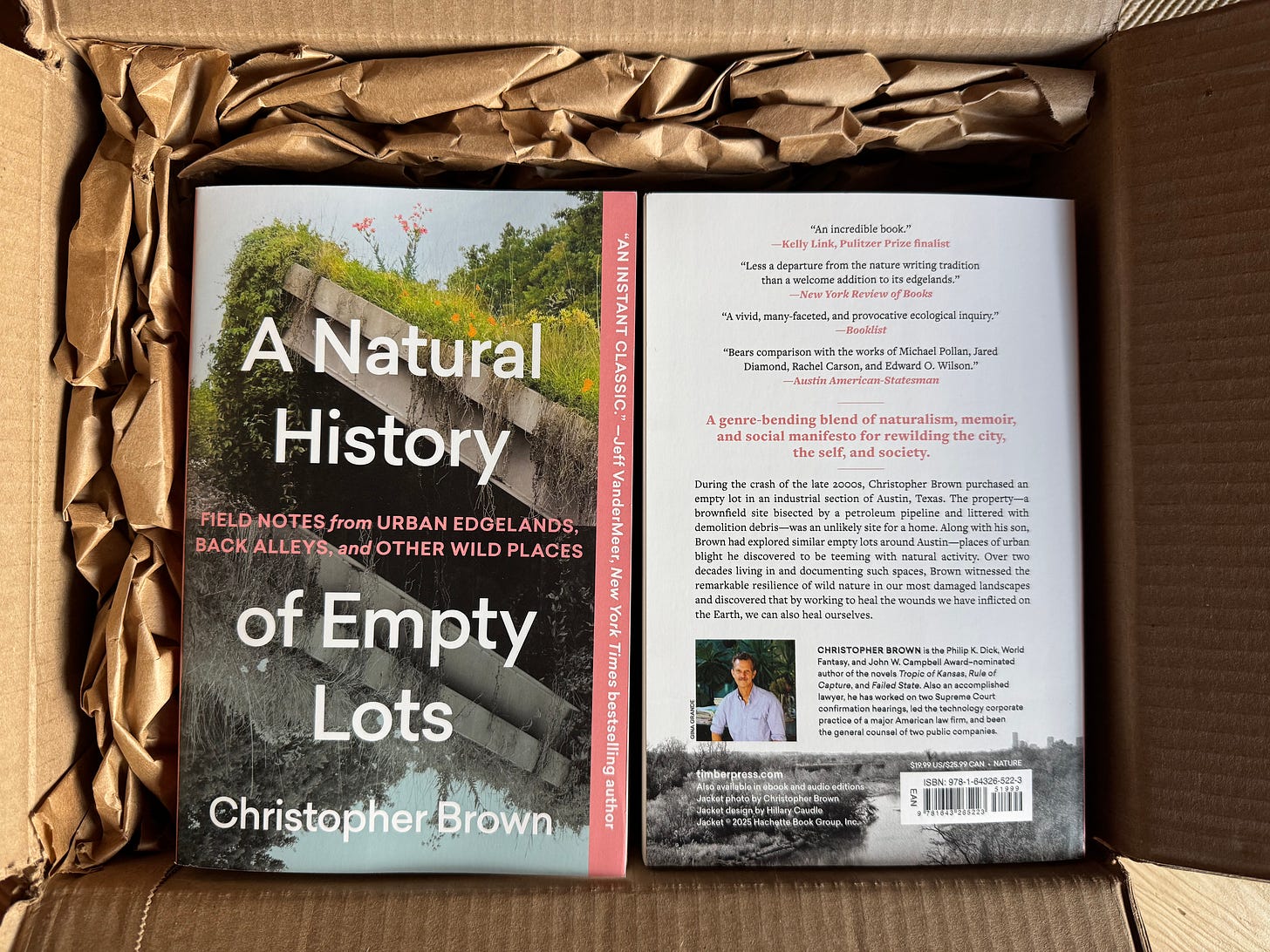

Empty Lots in Paperback

Friday’s mail brought me my author’s copies of the paperback edition of A Natural History of Empty Lots, and I’m delighted to report they look great, inside and out. Thanks to the team at Timber Press, including my editor Makenna Goodman (whose own new book Helen of Nowhere, a novel I think readers of this newsletter will love, is forthcoming from Coffee House Press in the U.S. and Fitzcarraldo Editions in the UK), designers Hillary Caudle and Sara Isasi, and the publicity team of Katlynn Nicolls, Melina Dorrance and Caroline McCulloch who helped get the word out. And bigger thanks to all the readers, librarians, booksellers and reviewers who helped make the hardcover edition such a success.

If you’re in Austin, we’ll be having a paperback launch party on the release date, October 7, at Alienated Majesty Books, which will include a screening of Brett Gaylor’s new short film Field Notes from an Apocalypse, and a panel discussion with a diverse group of local thinkers and activists about how we can go about the hard work of decolonizing and rewilding the future. Please join us if you can, and RSVP here.

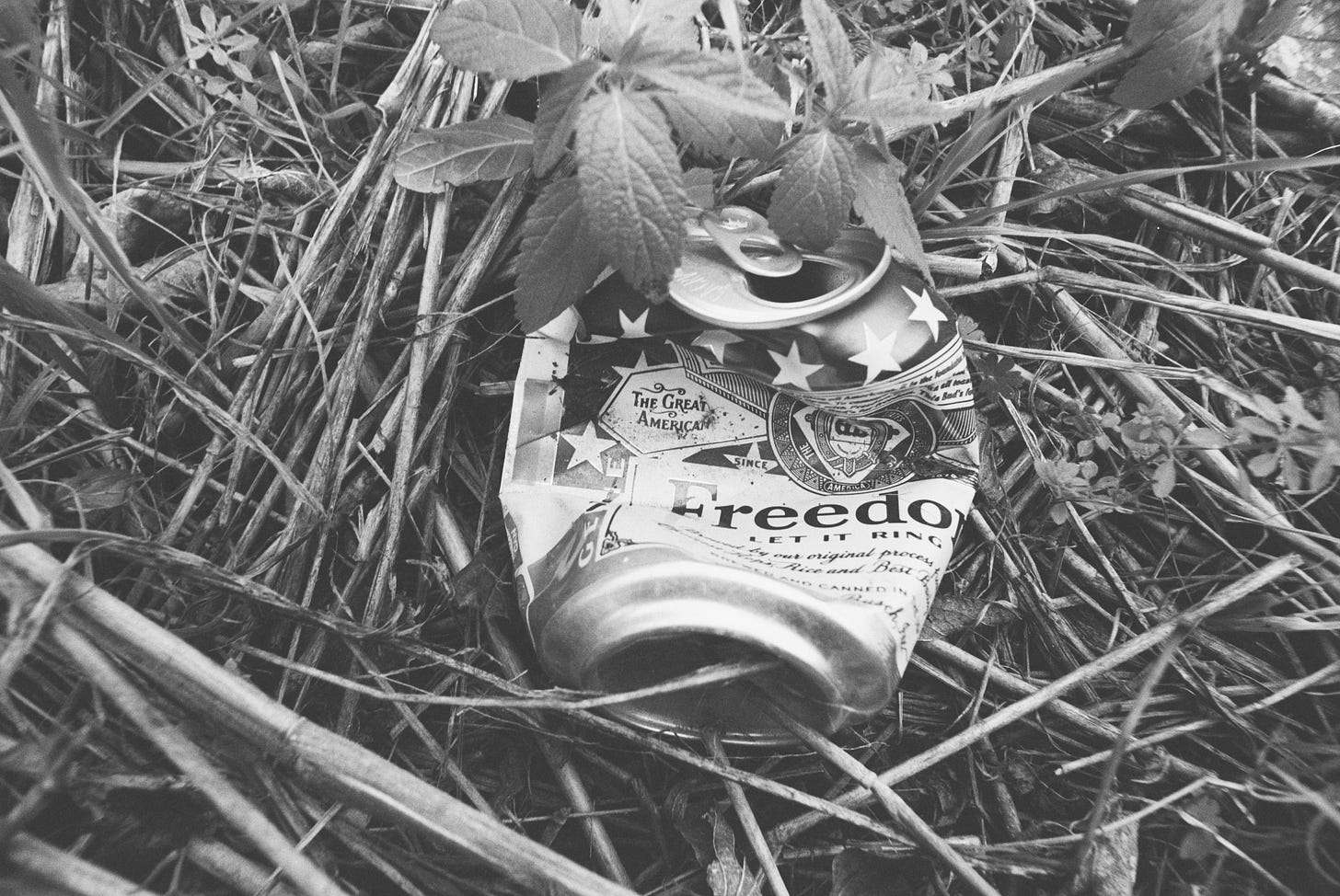

And just for fun, I’m going to do another preorder promotion for readers of this newsletter (especially new readers). If you preorder the paperback (or order any of the other editions already available) and email me your confirmation (chris-at-christopherbrown.com) and snail mail address, I’ll send you a bookmark in the form of a 3x5 print from the negative of one of the below film photos (your choice):

Alternatively, I’d be happy to send you one of 9 free copies I have to give out of the Audible version of the audiobook narrated by yours truly (while supplies last), or a copy of the print zine I did for the hardcover launch last September (also while supplies last), which includes an original essay and a reading list of other books in the genre.

Last week I learned that the book is on display at the Venice Architecture Biennale, part of this library Porch curated by the team at Places. Thanks to Boyce Upholt for the heads up—and keep an eye out for issue 1 of his new print magazine Southlands, coming next month (and including a short essay by me).

Nature Writing Class

I’m also excited to share the news that I’ll be teaching an online class this fall designed to provide a fresh take on “Writing the Natural World” through the Writer’s League of Texas: November 5, 6:30-9:30 pm CST. Whether you are interested in nature or place writing as independent genres, or in thinking in fresh ways about how nature and environment feature in your fiction or nonfiction, this class will aim to provide you new tools and have fun in the process. We did a panel discussion on these themes with WLT earlier this year, and it was a big hit. Please register here if you’re interested, and ping me if you have questions.

The Roundup

In other news:

Perito Moreno, one of the few great glaciers thought to be stable due to its unusual location in Patagonia (and a natural wonder my wife and I visited on our honeymoon), is shrinking.

They are trying to rewild the Venetian island of Poveglia.

The floods exposed 115-million-year-old dinosaur footprints in northern Travis County.

Tesla is also getting exposed in Travis County.

Hanging with the coyotes of Central Park.

At Harper’s, Lewis Hyde on “The Geological Sublime” (long read on butterflies, deep time, and climate change).

Field Notes friend Ed Park is finally on Substack with a cool new newsletter (that sort of revives his old blog).

Have a great week. Field Notes will be back after Labor Day.

Sorry to hear your part of the river has been discovered and is being ripped apart by the forces of development. It's not exactly urban sprawl but rather urban intensification with increasing numbers of multi-unit residences that pack people together in crowds that would drive me insane. I suspect it makes the sardine-people crazy, too.