Cozy catastrophes

We saw the first cliff swallows of the season last Sunday morning, dancing over the urban river. They’re one of the first birds I really took notice of when I started exploring this area two decades ago, because they are such impressive Anthropocene adapters. They build their elaborate dwellings on the sides of the bridges, perfect pustules of mud spackled onto the steel trusses, usually in huge colonies. Each of their little huts has a tubular entrance on the outside, and when you find the colony, usually on the morning side of the bridge, you can’t believe how busy they stay, coming and going in and out with manic energy to feed their young.

Sunday, with my own young one on my back, what I noticed as I tried to point them out to her is what artful foragers they are. Like the bats that live in the crevices under the Congress Avenue bride, they live off the insects that fly over the river and its surroundings, but the swallows are hunters of the day, and they do it with rare avian grace. They propel themselves with little bursts of wingbeats, and then glide like acrobats, working invisible corkscrew patterns through the morning air, devouring bugs we can barely see. They are the hardest animal I have ever tried to photograph, because they are so small, so fast, and never stop moving unless they are hidden from us inside their huts.

I thought about them Sunday night, as I set out on my own forage, my second big grocery run since the pandemic panic began. It’s weirdly ridiculous to feel that sense of danger in such a simple and convenient consumerist task as driving to the store to buy food, no matter how dangerous the bug is, or how fierce the competition will be from your fellow naked apes as they try to secure the supplies they need to make you think they are not animals. With all the trappings of civilization, we are less elegant foragers than those swallows.

I also thought about the opening scene of the 1971 post-apocalyptic movie The Omega Man, when Charlton Heston, the last survivor of a plague, roams the abandoned streets of downtown Los Angeles, taking whatever he wants from the stores, then returning to his barricaded brownstone to enjoy a whisky and some Bruckner. It’s only later that you learn he’s not the last man on Earth—he’s just learned to treat everyone else as zombified others. It’s the type of story Brian Aldiss called a cozy catastrophe—a fantasy of the world ending for everyone but one person, usually an educated white man, who revels in the bounty of dominion without competition.

Our current catastrophe is cozy in a different way, and a lot more crowded.

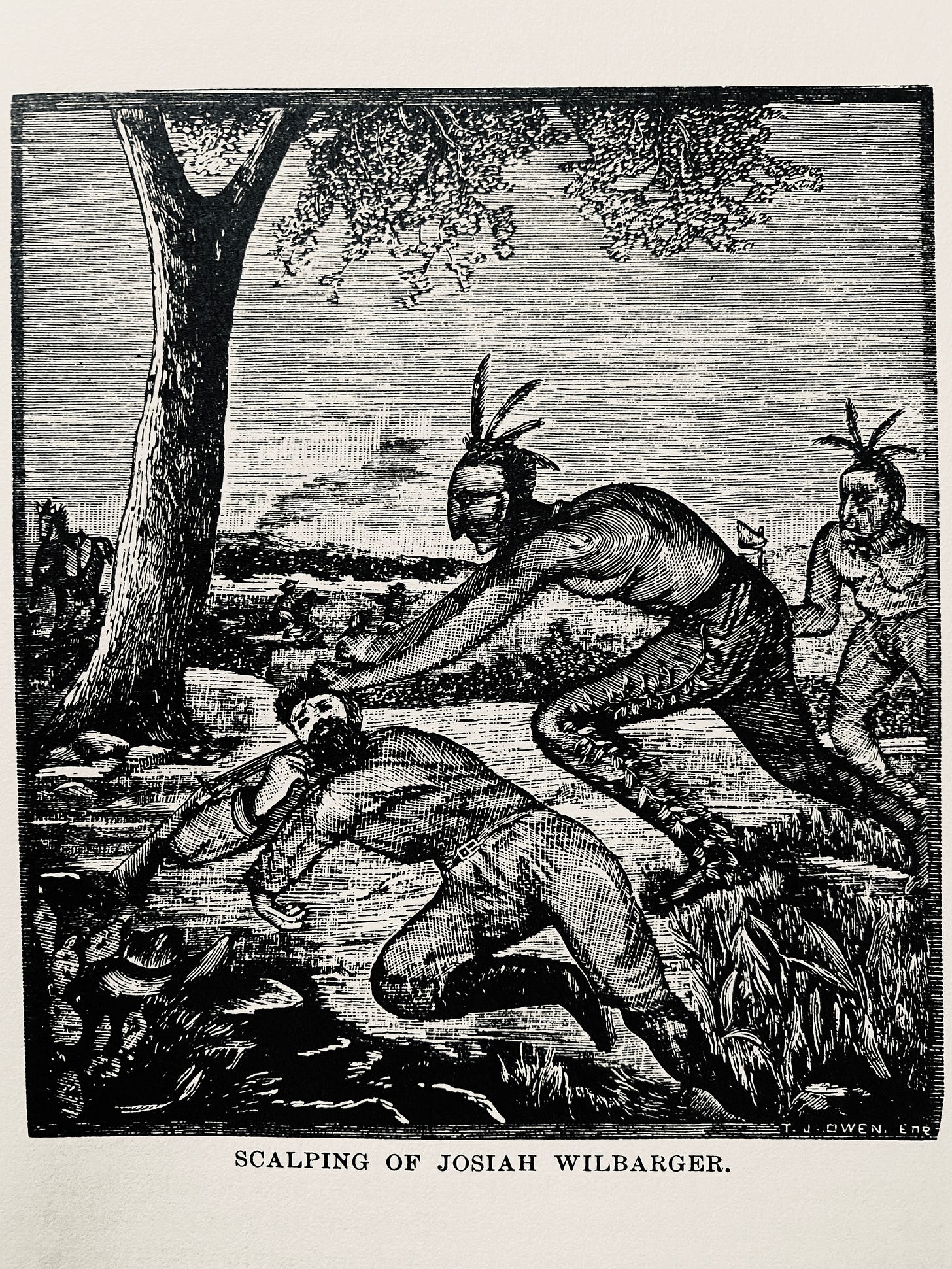

As I headed west, I thought about the forages of the first Anglos who settled this area, and the existing occupants they treated as aliens. Like old Josiah Wilbarger, who settled just downriver from here in 1830. His own brother relates the story in his insane 1889 compilation, Indian Depredations in Texas, about the time Josiah took some guys out to look over the land that would later become Austin. They ran into one of the natives, and then chased him off. Later, when they stopped to “noon and refresh themselves,” the Indian came back with his buddies, and ambushed them.

Wilbarger got an arrow to the leg and a bullet through his neck, and was left for dead. He was conscious as they scalped him, which he said sounded like distant thunder. They took all his clothes except for one sock. He tried to crawl to safety, eating snails in the bog while the coyotes howled nearby. When he woke in the night, he found “[t]he green flies had blown his wounds while he slept, and the maggots were at work, which pained and gave him fresh alarm.” But he made it, and, informed by a psychic vision, his neighbors found him the next day. He lived for another decade, until he bumped the hole in his head on a door frame.

Wednesday afternoon I broke quarantine to go look for the spot where this happened. I had remembered it as being further east of the city, near Hornsby Bend, which is named for the neighbors who saved Wilbarger. But the text describes the spot clearly, and it’s right in town, at the crossing of two of the main roads through northeast Austin, right behind the new urbanist development where the old airport used to be.

It’s the sort of place that’s easy to see on the satellite photos when you know where to look, but almost invisible from the roads that surround it.

I parked on the dead-end street that leads to Robert Rodriguez’s Troublemaker Studios, the gate of which has just one sign warning DANGER: HIGH VOLTAGE that you would only know is a prop repurposed as psyop if you already knew who the tenant was. There was another, even more secure facility across the street, what looked like a tech fab. Across from that was an overgrown field that leads to a thick stand of trees, behind the cable ropes that probably suffice to keep most people out.

I looked back at the car entering the suddenly open gate of the secure facility across the street, and stepped over the barrier into the tall grass.

The bluebonnets were all in bloom back there, and big yellow patches of some weedy wild mustard. The primrose was still coming up, in thick green bunches. The field slopes down toward where I knew the creek was, in the stand of trees, but the foliage all looked too thick back there. After a few minutes, I saw I was on a freshly overgrown path, animal trail or desire path or both, and followed its traverse down the grade, passing a couple of big manhole covers embedded in the earth.

The path disappeared, but I could see a way in to the creek. The poison ivy was coming up, some of it already big, but not so thick that you couldn’t avoid it. And with a bit of skinny simian yoga to get through the labyrinth of branch and bramble, I found the running water.

Urban creeks are generally pretty skanky, because most of what they collect is the filth we generate. The first thing I heard was the sound of a big turtle dropping into the water at my approach, and the first thing I saw as I looked at the water was a school of decent-sized fish. And on either side of the channel, thick stands of trees, the overstory dominated by tall skinny cottonwoods and one big cypress. There was trash in the creek, as there always is, and an old half-buried sewage pipe. But this was a place that had otherwise figured out how to mostly shut out human intruders. Every step required some variation of bushwhacker limbo, and the creek was too deep to cross without getting wet up to your knees.

After taking it in for a few minutes, I found my way back out. It was only then that I noticed the No Trespassing signs tacked to the tall trees. I looked back at the passage where Wilbarger’s brother describes the locations. On the way back to the car, I went up to the fence and looked in at the movie studio, with some big set building behind the old hangars that looked like a street corner from Once Upon a Time in Mexico, which I remember as being about Mickey Rourke and his pocket chihuahua.

On the other side of the creek, not two minutes drive, but a distance that down in the creek bed could have taken two hours on foot or much longer for a mortally wounded naked man, I found the spot that had to be where they had found Wilbarger. A clearing there at the side of the creek, at the base of the hill where the old road still heads in the direction of Manor, under the shade of some tall majestic oaks, within view of the backyards of a run-down 1970s apartment complex not unlike the one we lived in briefly when I was a kid.

The field I had walked through before was closer to where the ambush occurred. Wilbarger says it was the first blood shed in the conflicts between the Anglo-Texan settlers and the Indians. But he never bothers to say which Indians they were, just that they came from the “mountains covered with cedar” that must be hills of West Austin that are now covered with oversized suburban homes. I couldn’t find that answer in any other accounts of the incident. So I asked my friend Todd, a historian who specializes in the Indians of Texas, who I had seen just a couple weeks earlier when he was in town for a conference before the world fell apart. It probably wasn’t the Tonkawa, he said, who were known for collaborating with Austin and his colonists. More likely the Wichita.

Reading Todd’s book about the Wichita, I learned how they had thrived for centuries at the nexus of the eastern forests and the Great Plains, until the arrival of European disease decimated their population, along with a century of warfare. As a consequence, by the time the Wilbargers arrived, “land-hungry newcomers viewed them as little more than a nuisance.”

That got me thinking about another, wonkier book I recently read—The Great Leveler, Walter Scheidel’s sweeping examination of how pandemics (as well as wars and revolutions) led to the only real corrections to wealth inequality in human history. But never for long, and only by destroying wealth, not redistributing it.

Friday evening, as I went for a run during a break in the rain, I saw my first real urban forager since the crisis began. The most common foragers one sees around here are the people who work the empty lots and medians for fresh pecans in the fall, and the homeless men who collect cans for cash. This forager was digging around at the edge of the cloverleaf under the old highway bridge, pulling something from under a fallen tree in the right of way where the buried telecom cables are marked. He had a big grey plastic trash bin, and no car in sight, down at the end of a road that’s closed for construction as they turn the old highway into a toll road. When I came back out of the woods, he was gone, and I saw that what he had probably been collecting was dry kindling. It was only the next day, when I looked at the pictures I had snapped for this journal, that I noticed his pajama pants were printed with black skulls.

There are tent camps back in that wildlife preserve beneath the bridge, where the barred owls and the coyotes live, and the big moths emerge every year about this time. Until a week ago, you could see the tents through the leafless trees, but they are well-hidden now.

The data transmission lines that forager was standing over are part of the network through which the electronic money flows, at speeds that the ancient river nearby never approaches even at flood stage. In A Prehistory of the Cloud, poet and data engineer Tung-Hui Hu talks about how the major backbones of the American Internet are buried in the rights of way of the oldest railroad lines. Paths that follow the natural courses through the land that mostly would have been originally mapped by migrating megafauna.

As I walked in the woods this week, the perpetual motion machine of 21st century capitalism ground to a halt, the flow of electronic payments through those networks suddenly impeded by the need to freeze our most primitive biological networks. And all over the world, the reports started to come in of how rapidly nature was responding. The canals of Venice were suddenly clear.

After I passed the forager, I ran down to the river, and saw the cliff swallows out again. And I remembered the time a year and a half ago when I saw the crew out power washing their mud cup homes off the side of the overpass where the highway crosses the main creek the Wilbargers had followed toward the Hill Country that day in 1833. That route is now the path of the longest bike trail in town, also made from abandoned railroad right of way.

This morning, as I was composing these notes, I looked back at the map and learned the dystopian-looking facility I had seen across from the site of the 1833 massacre is the City’s Emergency Management Command Center, where they are managing the pandemic response.

As we stare into the abyss of the economic ruin this event will reap and worry about our neighbors and ourselves, freshly triggering our primitive drives for food and shelter in ways our ancestors understood much better, whether they lived like the Wichitas or the Wilbargers, you can’t help but wonder whether we will hear the messages nature is sending us, just in time for us to do something to ensure a healthy future for the planet before it’s too late. Maybe in this moment in which the usual transactional substitutes for human relationships have been suspended, we can paradoxically rediscover what real community feels like through the weird prism of social distancing. Or our relationships with our other neighbors.

*Here are those swallows before their nests were hosed off, in April 2017, with an overflying jet:

In other news, regarding the deserted traffic island I reported on two weeks ago, with the hawk nest in the tall trees between two onramps, I returned this week for a surprise: hawks with spring fever. I was jogging past just as the male swooped from behind the abandoned basketball hoop, flying crazy low to the ground, and then when I looked to see where he had landed, he had mounted the female in a bare branch. Sex with that kind of wingspan looks challenging. And the hawks looked like they didn’t want an audience, so I moved on.

This week’s bonus, for those who made it to the end:

My mother is a great forager, as was her mother. My theory is that she honed those skills when she and her mom and siblings had to live off the land for a time as refugees at the end of World War Two. I did not inherit that knack for knowing what’s edible in the woods. But when I got back from the mid-week expedition described above, I found Mom had sent me her favorite cookbook for foragers, inspired by last week’s Field Notes. Mom probably didn’t know how funny it would be to a science fiction writer to have a cookbook written by a woman whose other notable book won the August Derleth Award. But the cookbook is awesome, with useful tips on all manner of edible plants and methods for catching, grading, preparing unlikely animals like raccoon, squirrel, muskrat, opossum, snake and porcupine.

It contains what may be the best line I ever ever read in a cookbook:

“Drowning [chipmunks] out is simple with a garden hose, but very difficult without running water.”

Here’s one recipe, for one of the most common American weeds: