Upzoning the Conquista

Columbus Day in the Edgelands

I keep thinking the last of the late bloomers have come and gone as autumn settles in for real, and then there is something new. This week it was an explosion of plateau goldeneye, a plant with the awesome and allusive scientific name Vigueira dentata, presumably for the characteristics that cause some to call it toothleaf. This batch popped up in a neglected corner of our yard, a shady area that was full of illegally dumped construction debris when we got here a decade ago.

Like all goldeneyes, it’s native to the Americas. Super drought-tolerant and not too sun-hungry either, it’s one of those plants that have always been here that manage to persist in the negative space of the city, along the unmowed margins and at the weedy corners of empty lots. The tall goldenrod is another plant that conspicuously resists our dominion at this time of year, an even showier one that stands as tall as us. I saw huge patches of it in bloom Friday at the edges of the new toll road being paved over the ancient trail that connects the river with Walnut Creek and the Balcones Escarpment beyond. And one lonely plant on Thursday growing up in the right of way of some fiber optic cable.

The Spanish name for plateau goldeneye is Chimalacate, a Nahuatl name that means “shield cane.” The computer network of which that cable under the goldenrod is a part does not readily answer the question of why the Aztecs called it that, leaving one to guess, or imagine what it could be. It gives a sense of the range of the plant, to have thrived up here so far from the domain of the Aztecs, in an area that was dominated by the Blackland Prairie until the Texans showed up, an ecosystem that stretched in a long narrow band from the Red River to the north end of San Antonio, a zone of ecological transition between the Eastern forests and the Western plains. Ninety-nine percent of it has been destroyed by our subjugation of this landscape to the plow and the paver. That these plants persist in the face of two centuries of programmatic eradication in favor of grain monoculture and the urban machine it feeds reminds one how recent our conquest really is, and how tenuous.

On Monday the winds blew hard from the plains to the northwest, filling the air with dust from faraway Lubbock and the Panhandle. I hadn’t really noticed it until I went for a run, and fought it, and felt it, and then saw the intense haze around the skyscrapers of downtown. In the evening as we made dinner I listened to the song it made in the wind chimes we have hanging in the hackberry grove at the edge of the bluff, where the air comes up off the river.

These are not just any wind chimes. They are, as the manufacturer claims, “The Stradivarius of Wind Chimes.” They were a wedding gift from my late Uncle Fred, a vibraphonist who used to play with Max Roach and knew what qualified as a fine percussion instrument. He did not know they were made on the street where we live.

The wind chime factory is in an unremarkable 1980s prefab metal warehouse across the street and a few doors down. The proprietor is a reformed lawyer, and often as I am working in my trailer office I will hear our dogs barking their brains out and get up to find her exercising her tiny chihuahua outside our gate. Sometimes we visit. I take it as an indicator of the existential health of the pandemic era work from home crowd that she reports the fine wind chime business is booming during lockdown.

Monday was Columbus Day, a commemorative holiday that has not yet been renamed Indigenous Peoples Day by the state of Texas, but has been by the Austin City Council. A good day and week to be thinking about the long history of the conquest of the Americas. Maybe it was one of my encounters with my neighbor and her hilarious little dog that got me thinking about the natural history of the Chihuahua.

In the second letter he wrote to King Charles from Aztec Mexico in 1520, Cortez talks about the little dogs of Tenochitlan, and that letter is often cited as evidence that our Chihuahas are descended from the Techichi, the domesticated pets of the Toltecs, and as evidence that the Aztecs liked to eat them. When you go and read the entire letter, it gives you a sense of the wonders of the Aztec civilization, with its cities of pyramids built on islands connected by long causeways against the background of ancient volcanoes. And the scenes Cortez describes give you a sense of how intensely urban Tenochtitlan really was, even in the passage about the dogs:

This city has many public squares, in which are situated the markets and other places for buying and selling. There is one square twice as large as that of the city of Salamanca, surrounded by porticoes, where are daily assembled more than sixty thousand souls, engaged in buying and selling; and where are found all kinds of merchandise that the world affords, embracing the necessaries of life, as for instance articles of food, as well as jewels of gold and silver, lead, brass, copper, tin, precious stones, bones, shells, snails, and feathers. There are also exposed for sale wrought and unwrought stone, bricks burnt and unburnt, timber hewn and unhewn, of different sorts. There is a street for game, where every variety of birds in the country are sold, as fowls, partridges, quails, wild ducks, fly-catchers, widgeons, turtledoves, pigeons, reed-birds, parrots, sparrows, eagles, hawks, owls, and kestrels; they sell likewise the skins of some birds of prey, with their feathers, head, beak, and claws. There are also sold rabbits, hares, deer, and little dogs [i.e., the chihuahua], which are raised for eating. There is also an herb street, where may be obtained all sorts of roots and medicinal herbs that the country affords. There are apothecaries' shops, where prepared medicines, liquids, ointments, and plasters are sold; barbers' shops, where they wash and shave the head; and restaurateurs, that furnish food and drink at a certain price. There is also a class of men like those called in Castile porters, for carrying burdens. Wood and coal are seen in abundance, and braziers of earthenware for burning coals; mats of various kinds for beds, others of a lighter sort for seats, and for halls and bedrooms.

The letter also provides a useful reminder that the pre-Columbian Aztec capital, whose culture we render as barbaric in our persistent sense of religious and rational superiority, was, like the cities we live in and the ones on which the entirety of human civilization has been built, a human hive designed to sustain grain monoculture, including the production of corn—like the ear this Techichi is carrying.

In the same letter, Cortez describes the moment when Moctezuma admitted him and his men to the top of the Templo Mayor, a chamber filled with statues of the Aztec deities, many of them deities the Aztecs had taken from other peoples they had conquered. In a cinematic scene also described by Bernal Díaz in his account, Cortez brags to his sovereign how he knocked all the idols from their pedestals, and threw them down the steps of the pyramid stained with the blood of human sacrifices. Moctezuma warns of the consequences, that the desecration would anger the gods and deprive them of their powers, “and by this means the people would be deprived of the fruits of the earth and perish with famine.”

The deep connection of Aztec religious practices with grain production is evident in this astonishing description in which Cortez physically connects the two, without seeming to appreciate the symbolism encoded:

The figures of the idols in which these people believe surpass in stature a person of more than ordinary size; some of them are composed of a mass of seeds and leguminous plants, such as are used for food, ground and mixed together, and kneaded with the blood of human hearts taken from the breasts of living persons, from which a paste is formed in a sufficient quantity to form large statues. When these are completed they make them offerings of the hearts of other victims, which they sacrifice to them, and besmear their faces with the blood.

A gruesome communion, for sure, but maybe not really as distant as Cortez was inclined to think from drinking the transubstantiated blood of the host. We don’t know much about what our pre-Christian European rituals were, but it’s clear that ceremonies like the Eleusinian Mysteries were all about paying our debt to Demeter and Persephone for the knowledge of how to make crops grow. The history of human civilization is the history of agriculture and the urban culture and surplus wealth it generates, and the subjugation of other people, species and ecologies to sustain it. Something Cortez specialized in.

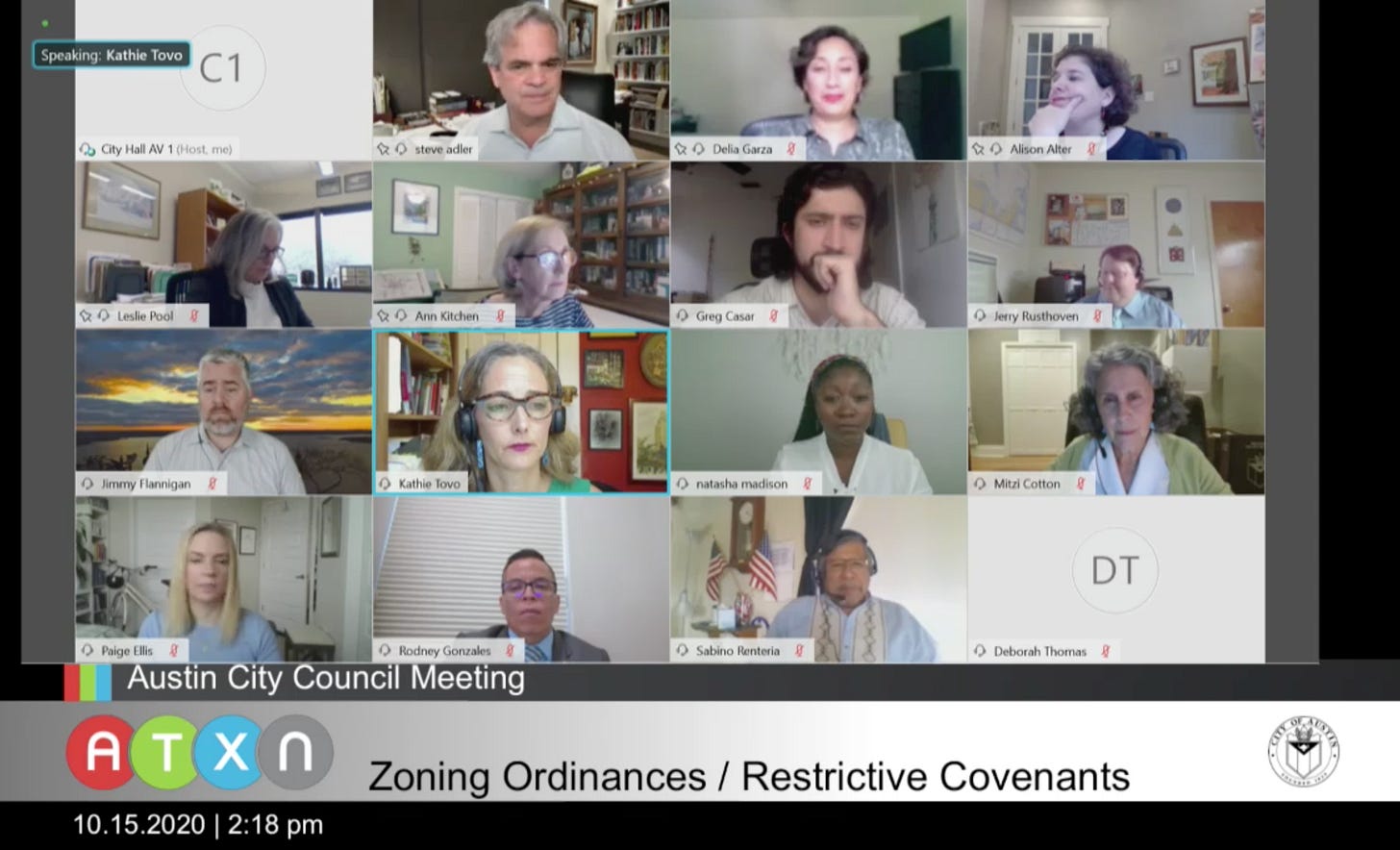

Chances are I was the only one thinking about all this Thursday as I waited my turn to speak before our City Council about a rezoning case. A City Council meeting during quarantine, conducted via Zoom, turning what is in normal times a pretty broken simulation of democratic process into a simultaneously hilarious and dystopian self-parody. The peak moment of futility of which was when one of the only two Council members to have voted in favor of our position at first reading began to speak, only to have her voice garbled into that of an electronic chipmunk.

The issue was an everyday one from the perspective of the Council: a proposed rezoning of a single-family lot to a multifamily residential category that will permit the construction of condominiums or townhomes, and thereby add more needed housing and increase the tax base. For me, it was mainly about fighting to protect one little pocket of urban wilderness. The lot in question is next to a 10-acre brownfield that the City for decades operated as a dump site and allowed to be used for the illegal dumping of toxic chemicals. It’s now owned by a nonprofit, Ecology Action of Texas, on whose Board of Directors I serve, and which together with its predecessor nonprofit has been restoring and remediating the site into an urban wildlife preserve dominated by ancient trees and the plants of the Blackland Prairie. A high density development above our site poses an existential threat to our restoration at Circle Acres, and so we joined with our neighbors, who are threatened with a change in neighborhood character and displacement, in fighting the project.

We won the day, thanks to the large and diverse coalition of citizens that spoke out on the project, so much so that one of the Council Members lectured them about sending her too many emails. But it was less of a victory than we thought, as the Council pulled a bait and switch after leading most of the people who had stepped away from work to dial in to think the proposal had been permanently tabled, and then turning that into a mere two-week deferment so the developer can have one more chance to salvage his deal before his contract runs out.

Having worked for and spent time advocating before legislative bodies for big chunks of my adult life, I have to say I was not prepared to witness the inadvertently transparent regulatory capture, as elected officials in a public meeting conducted via Zoom muted themselves to take what were obviously cell phone calls from lobbyists and connected advocates, and then in one instance unmuted to ask the lobbyist to approach the virtual dais and tell the Council what it should do.

It may be a stretch to think about this everyday zoning case as a quiet little ripple of the conquest of the Americas, but when you hear the people who are threatened with displacement tell the story from their perspective, as in this short video prepared by some of the neighbors, it conveys a much deeper history. And so long as people in positions of power and wealth are able to think about our relationship with the land on which we live through a purely transactional prism, that history will continue.

On this day

Two years ago Friday, we had a big flood that followed some intense rains. As I looked over the edge of the bluff to see how close the high water was getting to our home, I heard weird bird calls, and decided to go down and investigate. The reason I didn’t recognize the calls was that they were coming from a bird I had never seen—a group of wood ducks, including the remarkably plumed drakes.

What a beautiful sight. And yet what a sad one, too, when you widened the angle and saw what else was carried by those floodwaters:

One year ago this weekend, I found this gorgeous patchwork coyote walking through the frame of one of our trail cams, its coat taking on the colors of the autumnal forest.

This week I found a different animal changing colors: a common walking stick, resting Thursday afternoon by our front door. I wonder if she thought we couldn’t see her.

Further reading (and watching)

Cortez’s second letter to Charles V is worth reading in its entirety, and you can find a good long excerpt here via Fordham. On the subject of water birds, consider this wondrous vignette:

There was one palace somewhat inferior to the rest, attached to which was a beautiful garden with balconies extending over it, supported by marble columns, and having a floor formed of jasper elegantly inlaid. There were apartments in this palace sufficient to lodge two princes of the highest rank with their retinues. There were likewise belonging to it ten pools of water, in which were kept the different species of water birds found in this country, of which there is a great variety, all of which are domesticated; for the sea birds there were pools of salt water, and for the river birds, of fresh water. The water is let off at certain times to keep it pure, and is replenished by means of pipes. Each specie of bird is supplied with the food natural to it, which it feeds upon when wild. Thus fish is given to the birds that usually eat it; worms, maize, and the finer seeds, to such as prefer them. And I assure your Highness, that to the birds accustomed to eat fish there is given the enormous quantity of ten arrobas every day, taken in the salt lake. The emperor has three hundred men whose sole employment is to take care of these birds; and there are others whose only business is to attend to the birds that are in bad health.

A more extensive first-person account of Cortez’s invasion of Mexico can be found in Bernal Diaz’s The Conquest of New Spain, available in a good translation by John M. Cohen from Penguin, a copy of which you could probably find at your nearest used bookstore.

Our neighborhood wind chime workshop is called Music of the Spheres, and you can check out their retail website here. For those of you who live in more intensely urban settings and may think wind chimes are only for those who have yards, I should mention that my Uncle Fred told my son I was silly to hang ours outside. He had his in the hallway of his apartment on Riverside Drive in Washington Heights, and would let the deep vibrations suffuse that groovy space, the central room of which was a combination music room, library, and greenhouse.

The Austin American-Statesman has a wonderful piece in this week’s paper about the Black cowboys and cowgirls of East Austin, whose stable is just a mile or so up the hill from us, and how urban change is impacting them. The piece is accompanied by this beautifully done short video. “East Austin trail riders, facing gentrification, ‘aren’t going anywhere’,” by Bronte Wittpenn.

Over at Tor.com, I have a new essay up this week on the ways in which our newsfeeds have borrowed from the narrative of dystopian novels like the ones I write, and what that portends: “Dystopia as Clickbait: Science Fiction, Doomscrolling, and Reviving the Idea of the Future.”

And elsewhere on Substack, Andrew Liptak at Transfer Orbit has the transcript of a long, wide-ranging and fun conversation we had about my recent books, the utopia/dystopia dipole, and many other topics. My Midwestern mumbling comes through in a few spots where the transcription got garbled or ate a word, and my capacity for grapevine sentences is on full display in parts, but hopefully the meaning is clear throughout. Andrew plans to make a podcast version available soon. And if you are interested in the culture of science fiction, you really should be subscribing to his newsletter. Transfer Orbit: “Failed State's Christopher Brown on building utopias out of dystopias.”

Lastly, on the subject of conquests past, present, and future, please take a minute to watch this provocative PSA from the Tijuana Liberation Front’s Comité Magonista—a project of my friend the TJ-based writer and theorist Pepe Rojo, who crosses our militarized border several times a week:

Have a great week, and don’t forget to vote. We voted on Tuesday, the first day of early voting in Texas, and it felt good.

Fascinating array of information. What a wealth of knowledge. Thanks.