Chain link, Starlink and crypto-cats

No. 182

Saturday morning, back through the trees behind the old AM radio transmission antenna pictured above, I saw what may have been a jaguarundi. The likelihood that’s what it was, an expert would rightly note, is low, considering that an 18-year study concluded in 2021 that the species has been extirpated from Texas, and Austin is outside the jaguarundi’s historic range. But there have been sightings reported around here in recent years, including several outside Seguin at the beginning of this summer, and wildlife often break the rules our field guides lay out for them.

I was out walking our puppy, a Jack Russell Terrier our daughter named Fifi, exploring some pockets of interstitial green space I hadn’t visited in a while, including the expansive empty lot around the radio tower of old KNOW-AM. That field is less feral than it used to be, in an effort to keep the long-term campers out, but the zone it’s part of remains a quiet one where several secondary streets terminate in the backsides of light industrial blocks, and the verdant green corridor of the Colorado River is a literal stone’s throw away. Fifi and I had just stepped from the shade of a stand of tall trees when we saw the cat trotting past a row of shipping containers lined up behind a pottery studio. It was bigger than a typical domestic cat, with fur the color of graphite, a tail as long as the rest of its body, and short legs, almost the proportions of an otter.

We tried to get a second look, tracking around the edge-space between the chainlink and a parking garage, but it was gone.

Such a sighting would have been more plausible where we spent the week before, vacationing with extended family on the Texas coast in Cameron County. That’s where the last confirmed sighting of a jaguarundi in Texas was, in 1986, on State Highway 4 east of Brownsville—the road that now takes you to Elon Musk’s newly incorporated space colonization company town of Starbase. Calling that a “sighting” is generous, as it was actually roadkill, there where the road runs past the marshy preserves along the Rio Grande. Maybe that’s why the scientists are so confident in the accuracy of that report, of an animal that seems to have always been good at counfounding our perception.

The authors of the 2021 study that concluded it’s gone from here called Puma yagouaroundi “understudied, cryptic, small.” I first assumed they meant cryptic in the common sense—hidden, occult, maybe even evoking “cryptid.” But it turns out that for biologists, “cryptic” is a term of art, intended to denote species that are morphologically difficult to distinguish from other species but “biologically isolated.”

Not so biologically isolated, in the case of the jaguarundi, as to be incapable of interbreeding with other felines—or so some quick (but not definitive) research indicates. Maybe it’s the science fiction writer in me that got to speculating, after seeing the cat and considering the other recent sightings, that our putatively extirpated puny puma might have followed a path similar to the ghost wolves of Galveston. If otherwise extinct native red wolves have survived by interbreeding with urbanized coyotes, perhaps the jaguarundi could be similarly adapting to our post-colonial erasure of their habitat by mating with feral cats, and creating descendants adept at hunting the edgelands of our rodent-infested cities.

House cats gone wild mostly serve as agents in our elimination of biodiversity in the world, especially songbirds. I see them often, slinkily stalking at dusk into the green expanses beyond the chain link, after enjoying the easier meals of store-bought kibble left out front by the office staffs of the industrial businesses that line our neighborhood. Cats seem to be more dominant as predators around here lately, as our neighborhood has begun morphing into an entertainment district, and the coyotes have gone quiet, maybe moved on.

I used to see a lot of cryptic stray dogs back in these empty lots and woodlands at the edge of town, including a few that looked like hybrids of wild and domestic canines. I came to wonder if they were a glimpse of some emergent packs of the future—unevenly distributed manifestations of the end of the world slowly unfolding around us. A decade later, I learned the ghost wolves are real. The cats were ghosts already, in the stealth with which they roamed these spaces.

When we returned from the beach, contractors for the State Department of Transportation had begun site work on the giant berm near our home—a man-made ridgeline between two onramps whose weird animal users, urban cowboys and Anthropocene vistas I have chronicled in this newsletter. The new project relates to the expansion of Interstate 35 where it passes through downtown Austin, two miles west of us. To accommodate the growth of that clogged corridor, TX-DOT plans to take all the water that drains from the widened right of way (from Airport Blvd to Lady Bird Lake, for locals), channel it into a gigantic, truck-sized pipe buried a hundred feet under East Cesar Chavez that will carry it to a new pump station atop that berm, and spew it into the clean and clear stretch of the Colorado River below Longhorn Dam. The state’s original plan was no more “treatment” than a mesh filter to catch large debris, but the city has intervened, supported by advocacy groups like our Colorado River Conservancy, to redirect it to a new treatment pond that will ensure it meets drinking water standards before it hits the river, and perhaps provide an opportunity for some improved wetland habitat in the process. I still wonder what the pump station will sound like, and how it will smell. I already know why they put it on this side of town, and not the west side.

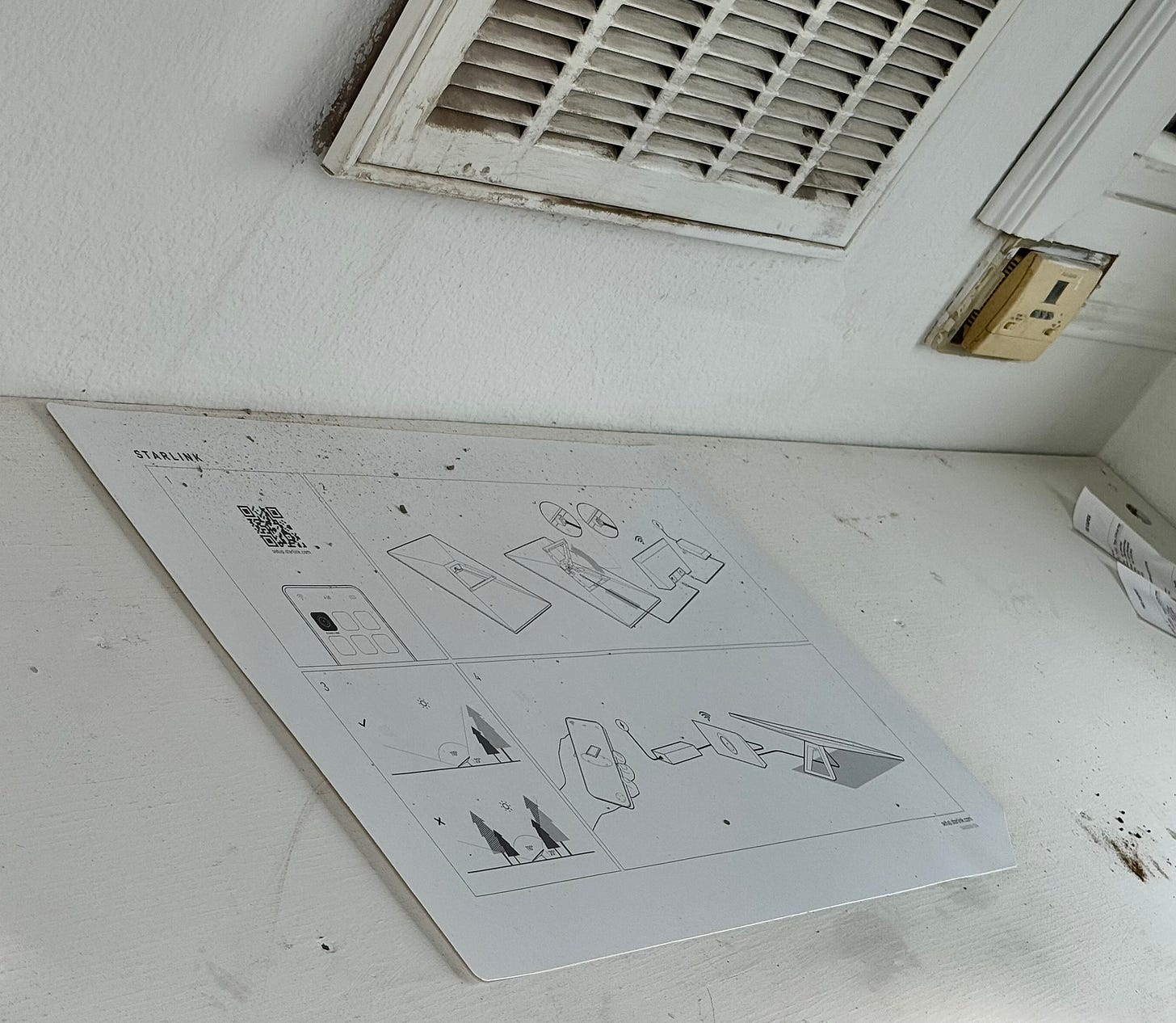

Fifi and I walked the site last Sunday, before they fully fenced it off. All mud, dried hard in the rough contours of heavy machine tracks. Toward the top of the berm there was a little container office. I peeked in the window and the only thing in there was a sheet of paper showing, in text-free visuals, how to connect your phone or laptop to Starlink. It felt weirdly like coming upon some abandoned ruin, on an Earth where the engineered machine systems have come to a stop, but the satellites we launched into orbit can still be seen in the night sky.

My waking dream of an emergent future of wild predators cross-bred with our emancipated house pets got me thinking of a cheesy Edgar Rice Burroughs paperback I read as a kid: Lost Continent, the cover of which featured a Frank Frazetta vignette of a 22nd century man and woman facing off against the jungle cats that have taken over the ruins of the future. A reminder that stories like that, usually packaged as warnings about the end of the world, express our unarticulated yearnings for the new beginning we could have—a rewilded future in which the balance between us and other life has been restored, and we get to live closer to our own nature.

Maybe exporting capitalism into space wouldn’t be a bad thing, if it left this planet behind in the process.

Summer Reading

Save the date: we’ll be celebrating the launch of the paperback edition of A Natural History of Empty Lots with an event at Alienated Majesty Books here in Austin on October 7, hopefully with a short film screening of a work in progress and a panel discussion about ruderal ecologies and radical futures. Watch this space for more info as the plans come together, and you can preorder the paperback (or get the hardcover, ebook, or audiobook narrated by yours truly) here at Timber Press/Hachette.

I ended up working most of our week in South Padre, and spending the time I had free playing with the kids on the beach, but I did get out to see some of the wild things with my 85-year-old nature nerd mom, including a visit to the new South Texas Ecotourism Center just west of Port Isabel. Created by Cameron County, STEC is a remarkable facility designed to provide visitors a platform for getting to know local flora and fauna, and a starting point for exploring the rich wilderness areas around the region—including this excellent interactive map to help you find them. (One of the big preserves is next to the facility, as pictured in the second photo above.) We got to meet Director Edward Meza and his exceptionally friendly and knowledgable staff, and will be back.

Congratulations to my bride and baby mama Agustina Rodriguez aka AgiMiagi for the successful installation of her insanely beautiful new sculpture, “Chorus,” in Dallas at The Village, and stay tuned for information about the dedication planned for September. The piece was trapped in Wimberley for six months while they figured out a legal route to get it to the site, and having heard Agustina negotiating logistics with trucking dispatchers, bucket truck drivers and state highway officials for the entirety of 5.5-hour drive back from South Padre, I have a new appreciation for what goes into moving oversized loads—especially tall ones.

On the subject of endangered and threatened species, the July 24 issue of the NYRB has an excellent piece by Michelle Nijhuis on what we choose to save, and why (paywall, but not for long, so bookmark it for later if you get blocked).

In wild canid news, the NYT had a Dora-ready report on the shoe-swiping fox of Grand Teton National Park.

In biodiversity crisis news, the EPA this week proposed re-approving the use of the twice-banned herbicide dicamba with “Roundup-ready” GMO crops. (Note the last line of the NYT report: “Last month, Kyle Kunkler, a former soybean industry lobbyist who has been a vocal proponent of dicamba, joined the E.P.A.’s Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention as its deputy assistant administrator.”)

And in free speech crisis news, the Austin Public Library’s amazing Zine Collection is under threat and not currently able to add new material due to legal concerns related to TX SB 412, “relating to defenses to prosecution for certain offenses involving material or conduct that is obscene or otherwise harmful to children.” If you’re local (or from elsewhere) and love to find weird new stuff at the library, please consider completing this online form to register your support for APL’s efforts to archive some of the most innovative and culturally rich content the community generates. More about the Zine Collection and its unstoppable curator Katrin Abel here in this Austin Chronicle piece.

Speaking of zines, my copy of Revelation Records’ new edition of Radio Silence: A Selected Visual History of American Hardcore Music by Nathan Nedorosek and Anthony Pappalardo just arrived in Saturday’s mail, and it’s almost as cool as maybe seeing a jaguarundi.

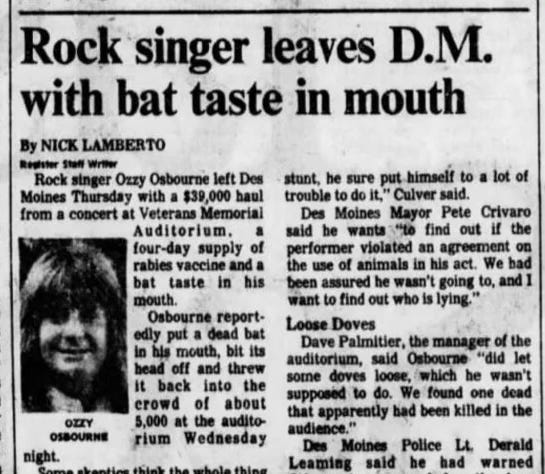

RIP, Ozzy, and thanks for the hometown memories—the time he bit the head off a bat onstage was in Des Moines during my senior year in high school. I wasn’t there, but several of my friends were, and one even still has his ticket stub.

The film photos in this installment of Field Notes were taken on my Ilford Sprite, a fixed shutter-speed plastic 35 mm camera that’s my preferred film camera for beach trips where I don’t want to expose my “good” camera to sand and salt water. If you’re looking for an easy point-and-shoot way to try the wonders of film, it’s a good one.

I took this shot of the summer sunset over our home on my phone:

Stay safe, and stay cool.

Think of our current concept of the ordering of the species as a sepia toned photograph printed from grainy 35mm film, developed by Linnaeus, taken with early model Leica cameras by amateur and professional biologists, a snapshot of 300 years illuminated by a single flash. We see only a frozen frame in the ongoing evolutionary whirl of life. But species morphology is a motion picture slowly revealing the changes of the plant and animal kingdoms through tens of millions of years. Feral cats mating with jaguarundi. Red wolves mating with coyotes. Life is patient and persevering; it finds a way for disappearing species to survive and go on in transmuted form. I have no doubt you saw a jaguarundi in its latest incarnation.

Oh, yeah, re the jaguarundi debate. Back in the mid-1960s, when the notorious Overton Gang kept things interesting around here (and, coincidentally, many of those safecrackers, pimps & gamblers grew up in your neighborhood)(whom I wrote about in "1960s Austin Gangsters," now available at many H-E-B stores, and elsewhere, but I love being at H-E-B), the infamous hoodlum Jerry Ray "Fat Jerry" James and his paramour, Betty/Joan/Joyce Taylor, kept a pair of jaguarundi at their homestead on Reveille Road in West Lake Hills. I like to think that their illicit offspring are out there foraging today.