Bunker herons and Okie noodlers

Saturday morning baby and I walked the dogs down into the floodplain and along the river. She’s learning more and more about the local wildlife, and gets excited about deer and ducks in a way only a toddler can. This is a good time of year to see deer, in midwinter, when the absence of foliage opens up longer vistas in the woods, and the deer are active in family groups. The coyotes are active now, too, and my neighbors came upon a trio earlier in the week right in the spot we most commonly walk, but baby and I were probably a little loud.

It’s been a grey and rainy week, a good thing to see this time of year as the early plants of springtime already begin to come up. Of course the main thing to come up is the downy brome, an invasive winter grass they say was introduced to stop the Dust Bowl, and that does a remarkable job of crowding out all the natives, just like we do. The woods are full of it, and so is our yard.

Some of the grasses, like the inland sea oats, compete well with the brome where it thrives. In other spots, like the rocky banks of the river, the brome can grow, and the switch grasses have taken over the waterline. The bluebonnet crop is coming on strong there this year, in earth that not too long ago was torn up to make concrete to build up the city.

Sometime before Christmas a group of do-gooders came out and tried to clean up the nature preserve under the bridge. Probably the folks from Keep Austin Beautiful, who do that once a year and leave the bags by the trailheads for the City employees to haul to the landfill. A worthy undertaking, especially as trashed out as that preserve has gotten during the tollway construction. We do our own similar clean-ups every once in a while, even as we learn, living by the urban river, what a Sisyphean effort that is, when every rain delivers a new mountain of flotsam from suburban backyards and construction sites.

The woods are full of all kinds of debris, much of it made by other species. My favorite are the bones the predators leave lying on the forest floor, like this deer pelvis baby and I encountered yesterday, and the feathers the big birds let fall from above. In the zone just over the first bank, the floodwaters leave huge timbers carried from miles away. They pile up atop each other in spots where the trees are too dense for them to push through, mixed in with railroad ties and lumber and a mountain of plastic bottles and misfit toys.

That human trash is undeniably ugly, even as it can produce wonder and moments of the uncanny when you encounter some object transported from the human domain into the atemporal zone of these weird woods, which manifest their creepiest qualities on grey winter days like today, sun and sky trapped behind a spider web of mustang vine as thick as your arms, working on pulling down all the trees that managed to grow tall in the rich and wet but loose and loamy dirt of the floodplain. We have a backyard collection of weird objects found out there. A plastic baby’s hand growing from an antler. The severed head of a pink flamingo attached to the fins of a model rocket. Anthropocene Easter eggs that tell the truth.

Perhaps it’s a distorted perspective from spending a decade living on a dump site, or from being the sort of person who chooses to live in one, to think that the whole world is a dump site. That even the most remote pockets of wilderness you can find, from Alaska to Patagonia, are shaped by our dominion. A profound cynicism about the true condition of the natural environment, that simultaneously generates a weird romance, and a surprising if muted optimism. The optimism of seeing the spiderwort thriving atop the piles of rubble left when they razed the mid-twentieth century version of the city to make room for this one.

When baby and I first stepped out of the woods and onto the riverbank yesterday morning, you could see the newly constructed parking garage rising above the treetops a quarter-mile upriver, where they are building a new office complex on the site of a former auto salvage lot. The kind of project that makes new urbanists smile, turning a junkyard into an entrepreneurial incubator where work becomes fun, and the only trash will be gently used PowerPoint slides and empty Topo Chico bottles.

It’s a weirdly science fictional sight to see the outline of that bunker for cars against the landscape of this river out of time. All the more so when you notice the tall bare cottonwood in the middle ground, grown up out of the alluvial accumulation of sediment, freshwater marine life, and human trash, and see the four big heron nests, each occupied by a great blue.

As I pointed them out to baby, one flew down to the water to scare off another, an exhibition of territoriality I don’t often witness in that species, a species that manages to thrive so well amid our domain that we take it for granted, even as every time one lifts off with an alien croak it’s as remarkable as it would be to see a pterodactyl perched atop that parking garage. And then I think how those herons have probably been fishing this river since the time of those people whose primitive stone tools one sometimes finds mixed in with the river rock, probably even longer than that. I wonder if they will still be here when that parking garage finally collapses under its own weathered weight, a few centuries from now.

In the afternoon I went back out and jumped a fence down the road to try to get closer to the rookery, only to find how well the spot had been chosen by those herons, a place you can’t get close to without getting into the water. Maybe next week.

The hunting and fishing report

Wes Ferguson has an amazing cover story in the latest issue of Texas Monthly on the hunting of exotic game in Texas. Exotics are unregulated, unlike the native herds of whitetail, which Ferguson explains are one of the few things the state holds in trust for the benefit of all as part of the commons. The piece centers around Ferguson’s visit to one particular ranch at the edge of the Hill Country, and his own decision whether to hunt some of the imported African wildlife while he’s there. It’s an excellent blend of cultural journalism, nature writing, and personal narrative, and I highly recommend it. “How Texas Hunting Went Exotic,” by Wes Ferguson, Texas Monthly, February 2021.

For even more exotic game, this week’s feed brought the news that a state lawmaker in Oklahoma has introduced a bill to legalize the hunting of Bigfoot, specifically focused on the Ouachita Mountains of southeast Oklahoma that are part of the legislator’s district. The bill would only permit trapping, not shooting, and I couldn’t help but wonder whether it would permit Sasquatch noodling.

It reminded me that my then-tweenage son and I once attended the premier of a documentary film titled Okie Noodling 2, part of a remarkable body of work the Austin-based filmmaker Bradley Beesley has produced about the weird American art of hand-fishing the muddy waters of the heartland. These guys wade into the rivers and lakes where monster catfish are spawning, go underwater, and shove their hands into the big holes they make their nests, and use their own arms as bait to capture the mamas as they defend their babies. A practice whose obvious ecological consequences are the reason it is generally illegal, but makes for undeniably amazing TV.

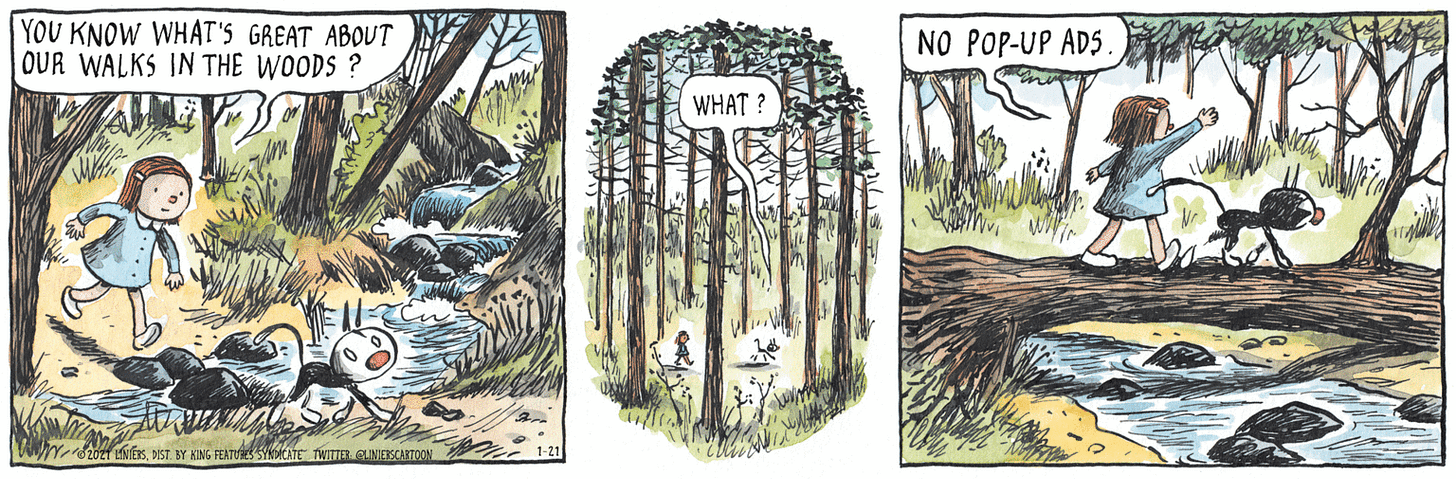

For a very different take on the wondrous monsters of the outdoors, I’ve really been enjoying the appearance of the Argentine comics auteur Liniers’ daily strip Macanudo in my feed, and in our daily paper. Daily newspaper comics somehow manage to keep going with what now must be a mostly online following, and the straight strips like Mark Trail and Judge Parker mostly now play to the comment trolls. Macanudo comes from a culture that produces hemerotecas, libraries exclusively devoted to the reading of old newspapers, and it’s wonderful to see a new strip emerge from that culture and infiltrate our own in translation, especially a strip so devoted to the love of nature. I especially dug this Thursday’s installment:

Macanudo, by Liniers, available for free at Comics Kingdom, the online feed of King Features Syndicate.

Thanks to Andrew Liptak at Transfer Orbit for tipping me off to Simon Winchester’s new book Land: How the Hunger for Ownership Shaped the Modern World, the audiobook of which (narrated by the author) I began to listen to this week. The book takes the form of the history of one particular piece of land, an acreage in upstate New York that Winchester bought in the late 90s. It’s interesting to hear an English writer’s take on that all-American narrative form, and to see how he uses it as the launching pad for a much deeper history. It’s a book I think readers of this newsletter might dig.

I was delighted and humbled to learn this week that my own latest book, Failed State, which came out last summer, has been shortlisted for the Philip K. Dick Award, among a slate of amazing nominees. The award is for distinguished works of science fiction published in paperback original form in the U.S., and until recently always included at least one mass market paperback, signifying its devotion in the tradition of its namesake to the idea that pulp fiction can produce great works of literary wonder. The winner and any special citations will be announced in April.

No exotics in this week’s trailcam, but plenty of reminders that some creatures like the invasive grasses of midwinter.

Have a great week.

Great read. thanks Chris.

The heron section reminded me of Paul Farley's poem "Heron"

"One of the most begrudging avian take-offs

is the heron's fucking hell, all right, all right, ..."

http://a-poem-a-day-project.blogspot.com/2014/08/day-768-heron.html

Had to smile too - the presence of "baby and I", colours the writing in unexpected ways.

Enjoyed! The strip brought two thoughts to mind: that I miss the incomparable Calvin and Hobbes and a quote from Gregory Bateson, one of the 20th century’s great minds. “The major problems in the world are the result of the difference between how nature works and the way people think.” Thanks for this Chris.