Black Nature Writing

Reading stories of braver solos

This newsletter is about walking alone in nature. Mostly with an inclusive idea of what constitutes “nature”—the degraded urban wilderness of empty lots, traffic islands, and the trash-strewn floodplains of rivers that flow through big cities. But it’s not as inclusive as I like to think.

I go into the woods or onto the river to feel like I am stepping away from society, into a different realm, tuning in to the non-human world. I see the signs of human impact in the landscape, but the connections I make are mostly with other species, and with the earth, air, sun and water. But recent events in the national news like the murder of Ahmaud Arbery for jogging while black and Central Park birder Christian Cooper’s experience having a white woman call 911 when he asked her to leash her dog have helped me appreciate more clearly the extent to which the outdoors is not neutral territory, but maybe the most segregated part of America.

The kind of urban eco-exploration I document here is a product of privilege. The privilege of being able to walk alone through the negative space of the city, often traversing private property, sometimes marked, sometimes not, through a landscape populated by men with guns and a religious fidelity to the idea embodied in the fence, without ever really worrying that something bad could happen to me. The reflexive confidence, accumulated over an adult life as a white male establishment lawyer, that my very status is the real passport this society issues, one that lets you mostly go where you want.

My walks often involve encounters with other solitary walkers. And in the fifteen years I have been exploring the zone along the Colorado River in East Austin, many of those encounters have been with people of color, usually enjoying the wild parts of their own neighborhood, like the guys pictured below digging nightcrawlers from Boggy Creek. But in a life spent outside, from the Big Bend to Alaska, from the Maine coast to the California coast, from the Boundary Waters to the Rocky Mountains, almost all of the other hikers and paddlers I have encountered have been white. It’s not because they are the only ones who enjoy life outside.

This week I looked at my shelf of nature writing and realized what a monoculture it really is. Classics of the genre, stories of canoe trips, guides to all manner of flora and fauna, books of cloud watching and wind collecting, romantic poetry and paper planetariums. A few Native American voices in there, but as soon as you ask the question you already know the answer: nature and the outdoors are a field of writing dominated by white authors celebrating one kind of diversity while mostly oblivious to another.

A few weeks ago a family member sent me The Norton Book of Nature Writing, a canonical anthology of exceptional pieces by more than 125 writers, most of them American, intended as a teaching text. Only seven of the contributions are by writers of color. That after an effort by the editors to expand from the original 1990 edition, noting in their introduction “the growing consciousness that there can be no fundamental distinction between environmental preservation and social justice, that human compassion and environmental sustainability are branches of the same tree, and that cultural diversity is one of the primary resources we have for ensuring biological diversity.”

I’ve written a fair bit about those connections, on my own terms. I’ve learned a lot in the past decade from neighbors who fight for justice at the nexus of race and environmentalism, and from my dear uncle, who in his last few years traded stories of our shared hometown with me that helped me understand the extent to which my childhood freedom of movement was something he never had as a black kid for whom even a paper route was a trip into the danger zone. But to my embarrassment, I had never really looked with clear focus at what colonized space the American outdoors really is.

This week I began seeking out nature writing by black authors, and found an array of powerful works that immediately sharpened my understanding of the very different ways in which we experience access to nature. I found writers who bring a much deeper and more intense sense of the history visible in the land, whose expressions of the joy to be found in those moments of satori-like connection to the non-human world transcend the usual reveries of this peculiar genre. And writers whose walks in the woods are haunted by a fear of more than snakes and bears. I have only just begun to wade into this body of work, but I thought I would use this week’s newsletter to share a few examples of the enlightening literature that’s out there, and encourage you to go read them and undertake your own explorations.

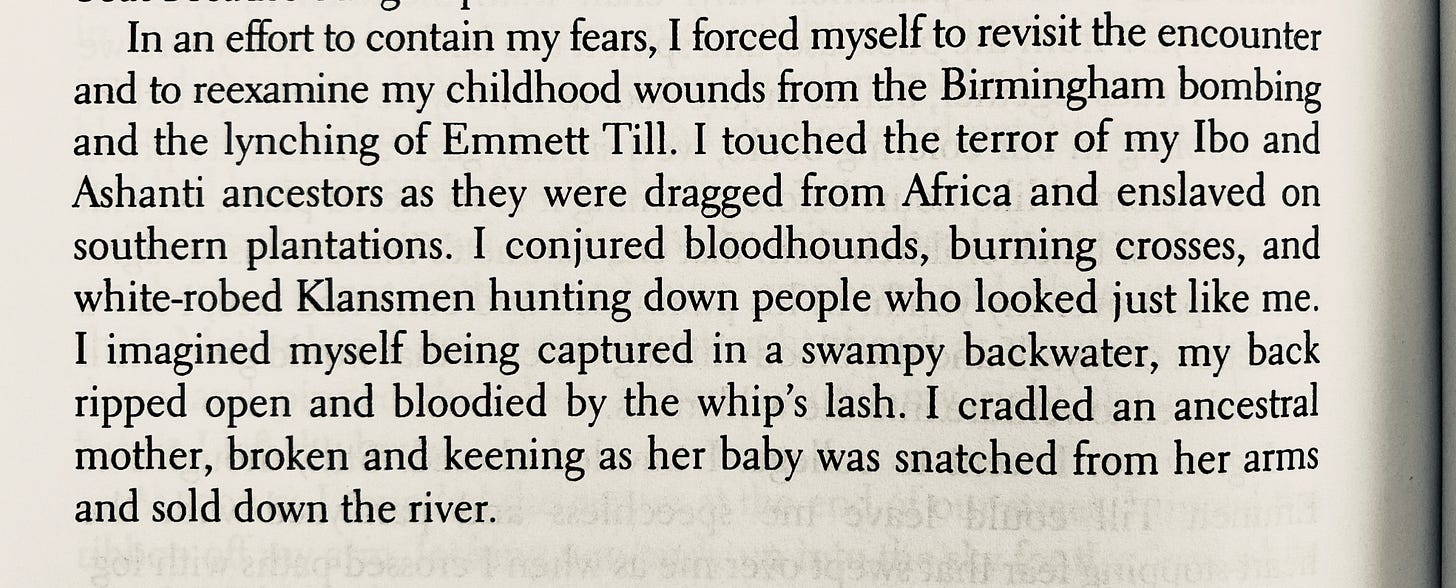

Evelyn White

Evelyn White writes about a lot more than nature, but her short essay “Black Women and the Wilderness” is one of the most powerful and succinct discussions I found of that difference of experience. She shares her intense fear at even the idea of going out outside the city, through a recollection of summers spent in a genteel and bucolic setting, the kind most writers covet, teaching at a mountainside writers workshop in Oregon’s Cascade Mountains. Showing through personal history why she was unable to join the students and other teachers in their daily excursions out into the woods and onto the river, even though she may have had even stronger yearnings than them to connect with what’s out there.

“My genetic memory of ancestors hunted down and preyed upon in rural settings counters my fervent hopes of finding peace in the wilderness. Instead of the solace and comfort I seek, I imagine myself in the country as my forebears were—exposed, vulnerable, and unprotected—a target of cruelty and hate.”

When she finally gets up the nerve to go on a river trip with her colleagues, her presence results in the boatman turning them down, claiming there are no more boats. So they go on foot, into the woods.

Lauret Savoy

Lauret Savoy is a geologist who teaches at Mt. Holyoke, and writes about landscape through a prism of deep history. Her book Trace is memoir through the mirror of environment, tracing her lifelong connection with the study of the land in parallel with her coming of age as one of its inhabitants, a woman of mixed African, indigenous and European ancestry whose childhood cognizance of racial identity she describes as being imposed on her long after she had looked at her skin in the California sun as a young girl, and connected her soul to the American rock through a family trip to Grand Canyon’s Point Sublime. Savoy writes with an easy grandeur grounded in a compelling personal story, suggesting the draw of natural history as an escape from racism: “nature wasn't something that would hate me.”

“Human experience and the history of the American land itself have, in fragmented tellings, artificially pulled apart what cannot be disentangled: nature and ‘race.’ It’s important to make connections often unrecognized, to trespass supposed borders to counter some of our oldest and most damaging public silences. There are so many poorly known links between place and race, including the siting of the nation’s capital and the economic motives of slavery. None of these links is coincidental. Few appear in public history. Many touch me—and you.”

Described by one reviewer as “John McPhee meets James Baldwin,” Trace won the American Book Award and the ASLE Environmental Creative Writing Award, and was a Pen Literary Award Finalist, shortlisted for the William Saroyan Prize, and nominated for several other notable prizes.

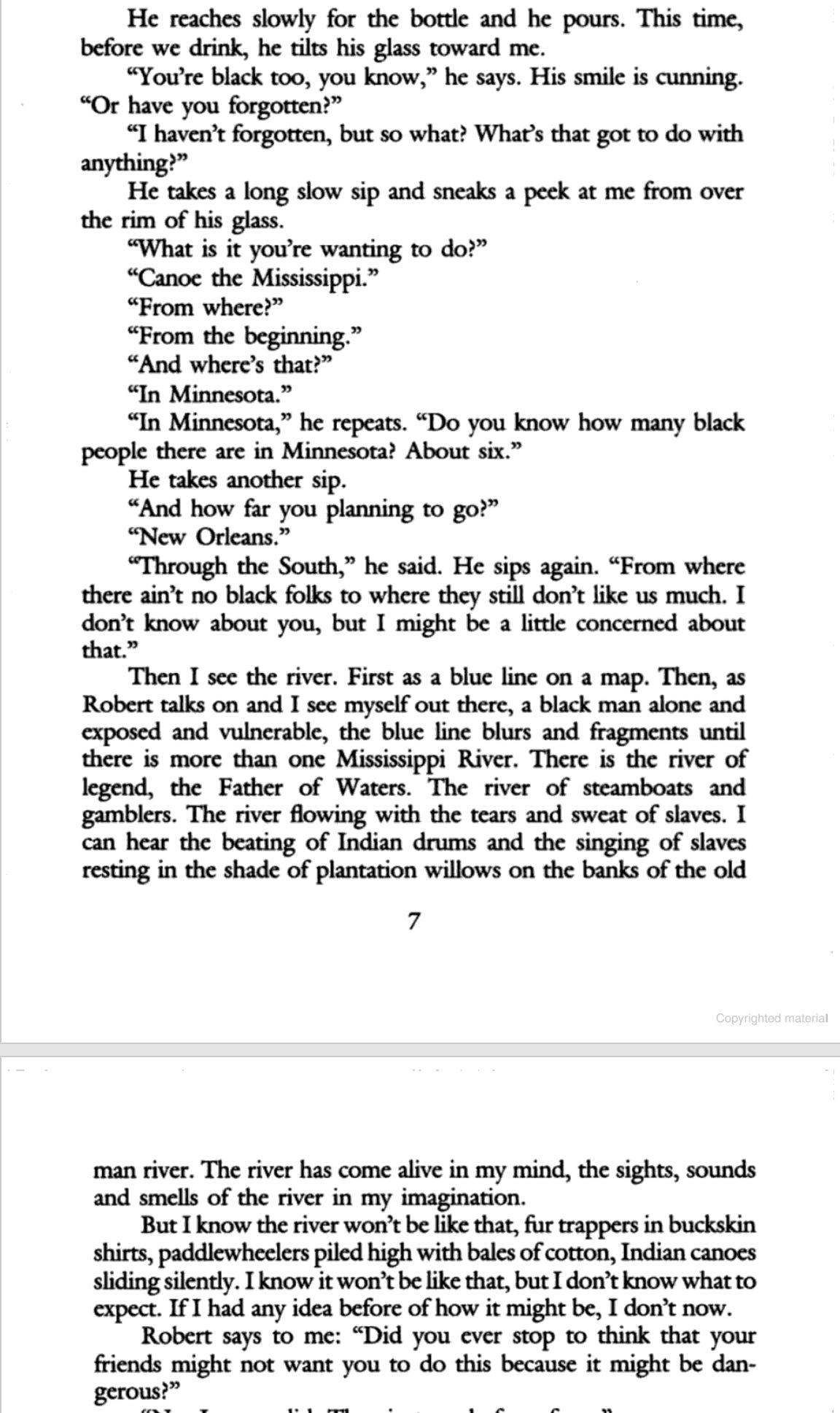

Eddy L. Harris

Eddy Harris is a St. Louis native who, at the age of 30 in the late 1980s, set out to canoe the full length of the Mississippi River—as a black man paddling solo. He chronicled this trip in his book Mississippi Solo, and then made the trip again 30 years later as a middle-aged man—this time with a camera crew, which produced the 2018 documentary River to the Heart. The epic trek on a route through the heart of America gives Harris’s book a powerful narrative line that lets all the parts of the story flow together—the personal journey, the intense social context, and the sublime natural history. Harris is a gifted storyteller who writes beautifully and perceptively, showing a keen self-awareness and eye for the character of others. Consider this passage, as he discusses his plans with an older mentor over whiskey:

Once I finish Mississippi Solo, I plan to dig into South of Haunted Dreams, Harris’s book about his even more courageous solo motorcycle journey through the Deep South, described as among the best books ever written about race in America.

I hope those of you who enjoy nature writing and the experience of the American outdoors will check these works out, and some of the other exemplars of this rich literature. They help us see how race is always there, even when there are no people around.

Further reading (and viewing):

Evelyn White, “Black Women and the Wilderness,” from Literature and the Environment: A Reader on Nature and Culture, edited by Lorraine Anderson et al. (1999), also collected in The Norton Book of Nature Writing (2002). Full text online here.

Lauret Savoy, Trace: Memory, History, Race and the American Landscape (2016).

Lauret Savoy and Alison Hawthorne Deming, eds.. The Colors of Nature: Culture, Identity, and the Natural World (2011).

Lauret Savoy 2014 interview with Conversations Around the Green Fire:

Lauret Savoy reading from Trace and in conversation at the 2016 Brattleboro Literary Festival:

Eddy Harris, Mississippi Solo (long opening excerpt at Google Books, with links to full text purchase options).

Trailer for Eddy Harris documentary, River to the Heart:

Camille T. Dungy, ed., Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry (2009).

— From “I am Black and the Trees are Green,” by E. Ethelbert Miller, collected in Black Nature.

Really important, thank you for highlighting these authors.