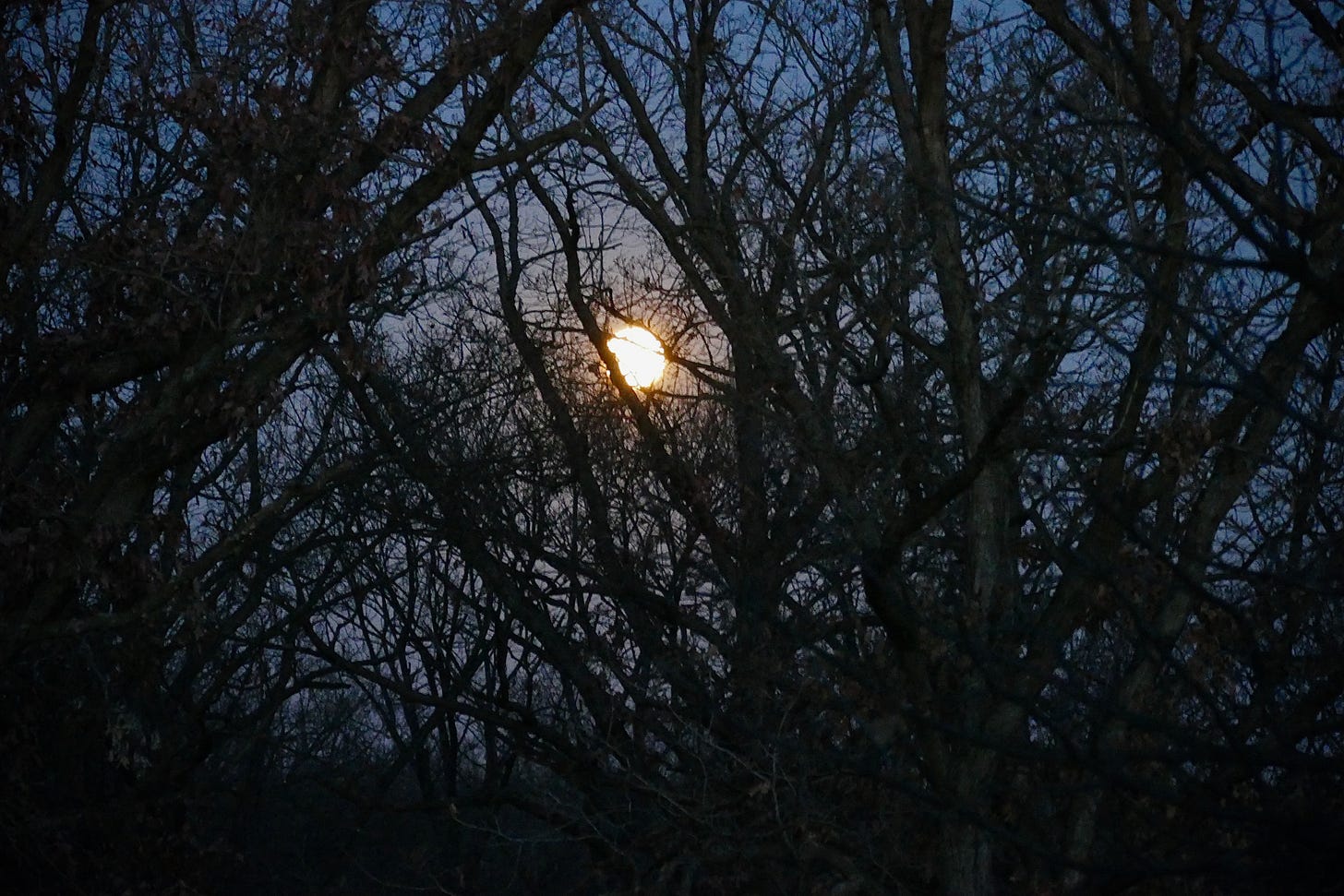

Autumn in the avigation easement

I heard the first barred owl of the season Thursday night, down in the woods behind the door factory, two days after the autumnal equinox. Just one lone bird, calling every twenty seconds or so, that distinctive hooo hooo hoo-hoo. The Audubon site says “the rich baritone hooting of the Barred Owl is a characteristic sound in southern swamps,” a description that embeds just a little bit of all-American folk horror. If you have ever had a close encounter with one of these birds, whenever you hear them close by you will see their eyes in your head.

That enigmatic stare of the flat-faced raptor sticks with you. No wonder those alien abduction stories often start with dreams of owls.

The first time I walked down alone into this little pond where the drainage off the nearby industrial parks piles up the trash at the headwaters of a gnarly creek, I saw one, sitting up there at dawn on one of the branches of the willow trees that grow tall from that skanky water. It didn't seem particularly pleased to see me. But it was a fresh confirmation of what I intuited about this place, before I even made a home here, that it is a place where the wild persists in the heart of the city only so long as it is protected from the presence of humans.

That sense that by your very entry into the woods, even alone and quiet, you are taking away their magic, is a tough one to process. But it makes every call of the owl more special, more endangered. The sound of a world that is being crowded out by us, even from the last little redoubt it has found in the zone where the city excretes its filth into a spot it thinks cannot be put to productive use.

A Natural History of DFW

As a productive unit myself, I have spent a lot of time over the past decade traveling through the weird interzone of Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. This week’s Facebook memory bot reminded me of the time three years ago when I made DFW my final destination, spending a long weekend in an airport hotel attending an SF convention while promoting my book Tropic of Kansas. When I clicked through to the blog post I wrote at the time, I realized it was an early experiment in these Field Notes (complete with the name), and a curious window into the pre-Covid world of business travel. So I thought I would re-post it here in full:

Sunday morning field notes from an airport hotel

September 25, 2017

The view from the fifteenth floor of the airport hotel looks out through a frame of pebbled concrete bolted to the structure. The pebbles are shades of pink and grey, harvested from local rock to make the brutalist sun-shading of the 1970s. I wonder how long the rock was there in the earth before they harvested it to create a place for business travelers to sleep between flights and meetings.

The window looks out onto a wide ancient plain between the forks of the Trinity River which has been almost entirely converted into a platform for launching hairless apes into the sky. Sixty-five million of them a year on more than two-thousand flights a day. They start coming at dawn and never really let up, making their own tunnels of wind just over the hotel, lined up in air traffic controlled constellations of avionic light threaded out across the eastern sky. Wide freeways lead to the airport from every direction, and to the parking lots of the seemingly infinite number of corporate hotels, identical office parks and shitty chain restaurants that append the complex, terrestrial mirrors of the network of hundreds of other airports that send the planes here and accept its departures.

I brought my trail running shoes for my weird weekend in this zone, and as I look out the window I imagine lines through the green space allowed by this Anthropocene overlay that straddles two counties and four muncipalities. There is an empty field right down there, a triangle of maybe four or five acres. In the field are twenty-seven bales of hay faded to grey, left there a long time ago, hidden at ground level behind the towering sunflowers of late summer. On Friday as I arrived men were laying a new road next to the field, preparing to pave it with every square foot of impervious cover the municipal development code of this particular suburb allows.

The water towers of Irving, of which there are many, each feature an image of wild horses running across these plains. And as I jog over the fresh-mowed Bermuda grass that grows in the rights of way, I imagine when it was like that here, with herds of fast mustangs roaming free, ready to be harvested like found money by enterprising pioneers. I am old enough now to realize how recently in time that was, and maybe even how brief a period a time of this place between the rivers was, because really the horses were as invasive as the imported grasses under my feet, an accidental gift of the Spaniards to the people who had walked here from the other side of the world.

Running along the grassy median of the road that follows the southwestern fenceline of the massive airport, you can see the people driving out of the brand-new subdivision of custom homes opposite the outer edges of the tarmac, and you can see that many of them are people who just got here from the other side of the world, or from the other class realities of this country. The sort of people who are not deterred by the signs in the lawns warning of the avigation easements encumbering the houses, agreements in advance to endure the noise of low-flying aircraft. They will not be here long, in these way stations on the path to American affluence.

Go mustangs, say the ball caps of the preppy old white people riding their BMWs to the SMU game.

On the other side of the George W. Bush Presidential Freeway, I noticed another wide field. As I stepped off the turf to cut through to it, I found native grasses coming up in a spot along the edge that evaded the bulldozers. The gentle grade of the field beyond that led up to an old billboard painted over black, accidental abstraction in a zone given over entirely to the self-expression of corporate persons. As I stopped to take a picture, a big hawk lifted off from the light armatures at the base, headed for a stand of exotic trees over there by the office park.

I came here for a weekend conference I thought was about imagining better futures, or at least other futures, but turned out to mostly be just another celebration of the repeat consumption of juvenile narratives of wonder by adults seeking escape from lives in the cubicles of those climate-controlled buildings. And on the last morning when I look out the window at the terminal to the sky, I realize this is that future that our predecessors imagined. I also remember the creek I saw flowing under the airport perimeter fence, and the prairie grasses I saw there holding out in a few square feet that the spreadsheets missed. I wonder how long ago it was that this plain was made by water, and whether these concrete creeks will overflow and drown the office parks sooner than the engineers think.

Protect Montopolis

If you are among the many readers of this newsletter who live in Austin, I encourage you to check out this excellent short video by Montopolis resident Annie Gunn about the threat one of Austin’s most remarkable brownfield restorations faces from a proposed upzoning of an adjacent single-family lot. I have written about Circle Acres here before, and I serve on the board of directors of Ecology Action, the nonprofit that owns and maintains the project. In the video, Circle Acres Operations Manager Eric Paulus explains the troubled history of the land, and how the proposed project could undermine the years of work that turned this dump site into a nature preserve.

If you are an Austin resident and want to help protect Circle Acres, and the wide Montopolis neighborhood, please consider writing your City Council Member (or the whole Council) and urging them to oppose the rezoning of 508 Kemp Street. We just need one more vote.

Bonus mantis

Tuesday afternoon I came upon this beautiful and bad-ass praying mantis hanging out at our front door. They are such remarkable and freaky creatures. Maybe because of the angle, it was the first time I really took notice of those jagged protusions of death along the forelimbs—tibial spines, I later read, used to aid in the ensnarement of prey. I also learned that, like an owl, a mantis can turn its head almost a full 360°. The mantis only has one ear, really just an eardrum located on the ventral side of the abdomen where the four back legs attach—right where you might imagine a belly button would be.

Most surprisingly, I learned that the mantis has five eyes. I had only noticed the two big green orbs, which you never forget once you see those cartoonish black dots aimed at you. “Pseudopupils,” explain the experts. Like us, the mantis hunts primarily by sight, scanning the full range of vision perceptible to the 10,000 photoreceptors of those big compound eyes, and then moves its head to bring the prey into higher resolution with the fovea at the front of the eye.

Here’s a video of that same mantis a little later on Tuesday afternoon, holding perfectly still as the baby pillbugs race by.

This research on praying mantis anatomy led to me to some weirder corners of the Web than I expected, including a site that sells live mantises as pets, and claims they can be trained. The site is full of aggressive little cookie injectors, and lots of gratuitous wtf no doubt designed as SEO bait:

In insects the part of the nervous system that moves each pair of legs is located between them in the thorax. That's why a cockroach without a head can still run away, or a Praying Mantis will still copulate without a head.

I’m not sure what to make of the fact that, when you Google the company name listed on the “About Us” page, it turns up a uniform store in the Bronx.

“Feed me, Seymour?”

Have a safe week.

Broad ranging and well written post. Wonderful information.

What’s the latest on Circle Acres?

Thanks, I look forward to reading your comments every week!