An Anthem for the Cicada Killer

No. 184

Friday morning as I was sitting alone in the waiting room at the car wash near our home, flipping through the weird selection of basic cable channels and tempted to pick up the dog-eared Joel Osteen book on the coffee table, I saw a cicada killer fly up to the glass door, gently probing it like a tiny helicopter trying to find its way through the invisible forcefield. I’ve seen a lot of cicada killers this summer, probably because we had a healthy crop of cicadas, and because I’ve learned to notice them lumbering through the periphery of my reality. They are the Clydesdales of wasps: bigger than bumblebees, with menacing stingers you can see from twenty feet away, and capable of hauling heavy loads. I’ve seen more than one carrying a freshly-paralyzed cicada twice its weight through the air, headed back to the nest chamber where it will lay an egg on its captive and then seal the chamber with dirt. A day or two later the grub will emerge, and begin its life eating the chitin-cased monster mom has left for it.

A shack next to a parking lot off a major urban thoroughfare seemed an unlikely place to see such a bad-ass bug. Most of the cicada killers I’ve seen were in our feral yard, where I first learned what they were after seeing one crucify her prey on the spokes of my wife’s bicycle one hot summer afternoon. But a little research indicates Sphecius speciosus is well-adapted to urban environments, tolerant of desiccated zones of full sun and adept at using sidewalks and other concrete slabs as structural enhancements for its burrows. Looking in my own photo archive, I found evidence of just that—a video from 2022 of one navigating a driveway. It seemed odd at the time but now I wonder if its nest was nearby.

The cicadas on which they live also seem to be holding out, though a review of recent reports suggests population numbers are declining overall, a dozen North American species of cicada have disappeared since colonial settlement—one of them recently—and there’s concern their current abundance is no guarantee of survival.

When the cicada killer flew off, the Wounded Warrior ad finally ended and I got to see what movie was on. I had flipped to a channel called Outlaw, which looked to be all Westerns all the time. It came on mid-scene, just as an aged but still tough-looking Randolph Scott shot and killed Warren Oates and his gang-mates while Mariette Hartley watched. Then the end-credits rolled and I realized it was the one Sam Peckinpah movie I never saw. I got to imagining an alternate timeline in which Peckinpah made nature films, like some shitfaced high desert horseback Cousteau. Human nature-nature films that mined the deep Anthropocene, in the spirit of that scene at the beginning of The Wild Bunch where a group of young kids trap some scorpions around the mouth of a fire ant mound and watch the orchestrated carnage that follows.

Earlier that morning while I was walking the dog, I found a disco ball by the side of the road, more than half its mirrors gone. It was in a spot I’ve passed hundreds of times over the course of 15 years, in a shadowed patch of dirt behind a mysterious shed next to the ruins of the bar they called el Agasajo (rough translation: “the royal treatment”). It might have just been dumped, but it looked like it had been there forever. A relic of prior inhabitants who had more fun here than we did.

Later in the day, my wife told me about the theory she had heard, convincingly presented, that time is actually, truly accelerating. In order, at least one author theorized, to accelerate the arrival of humans more capable of caring for the planet.

A week earlier, on the Friday morning that began Labor Day weekend, I joined a “stewardship walk” in our neighborhood wildlife sanctuary organized by staffers from a local parks nonprofit. Our group included representatives from the City Parks Department, two other folks from the river conservation and environmental nonprofits I work with, and a handful of other neighbors who love this weird pocket of urban wild.

Like a lot of the lands cities set aside off the tax rolls as habitat for other species, it’s a former industrial site adjacent to transportation infrastructure, such that the portal you pass through to enter the preserve looks designed to deter you:

But if you brave that brutality and keep walking, you don’t have to go far before you find some remarkable vignettes that let you see how rapidly an urban river corridor can rewild with little more assistance than being left alone—in this case a place that 40 years ago was an industrial gravel dredging site:

Along the main trails we also came upon the extensive camps that have been set up in the preserve over the summer. One of the Parks managers explained that most of the folks we encountered had relocated from a big camp immediately below the dam, which had to be evacuated during the July floods. He also explained to us the processes the city tries to deploy to help such folks get housing and other assistance at the same time as it compels them to clear out.

At one spot, on a rapidly eroding river edge, someone had somehow transported a gigantic metal tank harvested from the ruins of the old dairy plant a quarter-mile upland and turned it into a shelter. It looked every bit like a marooned spacecraft. Or one that had splashed down, and was ready to safely float downriver to the Gulf with the next flood.

We saw some cool birds and some scary dogs, made new connections, and discussed how best to organize to protect this place and other local pockets of riparian wild, including some of the more complicated issues around how to balance the needs for human and non-human habitat, and simpler questions around how to manage the trash people dump and the trash the waters leave behind. We left with a worthwhile list of community initiatives, but I couldn’t help but feel we’d just toured a pocket of unevenly distributed future in which personal prosperity and healthy lands are as endangered as most of the wildlife. There are only a few species like the cicada killer that can adapt to live at the edges of our concrete dominion.

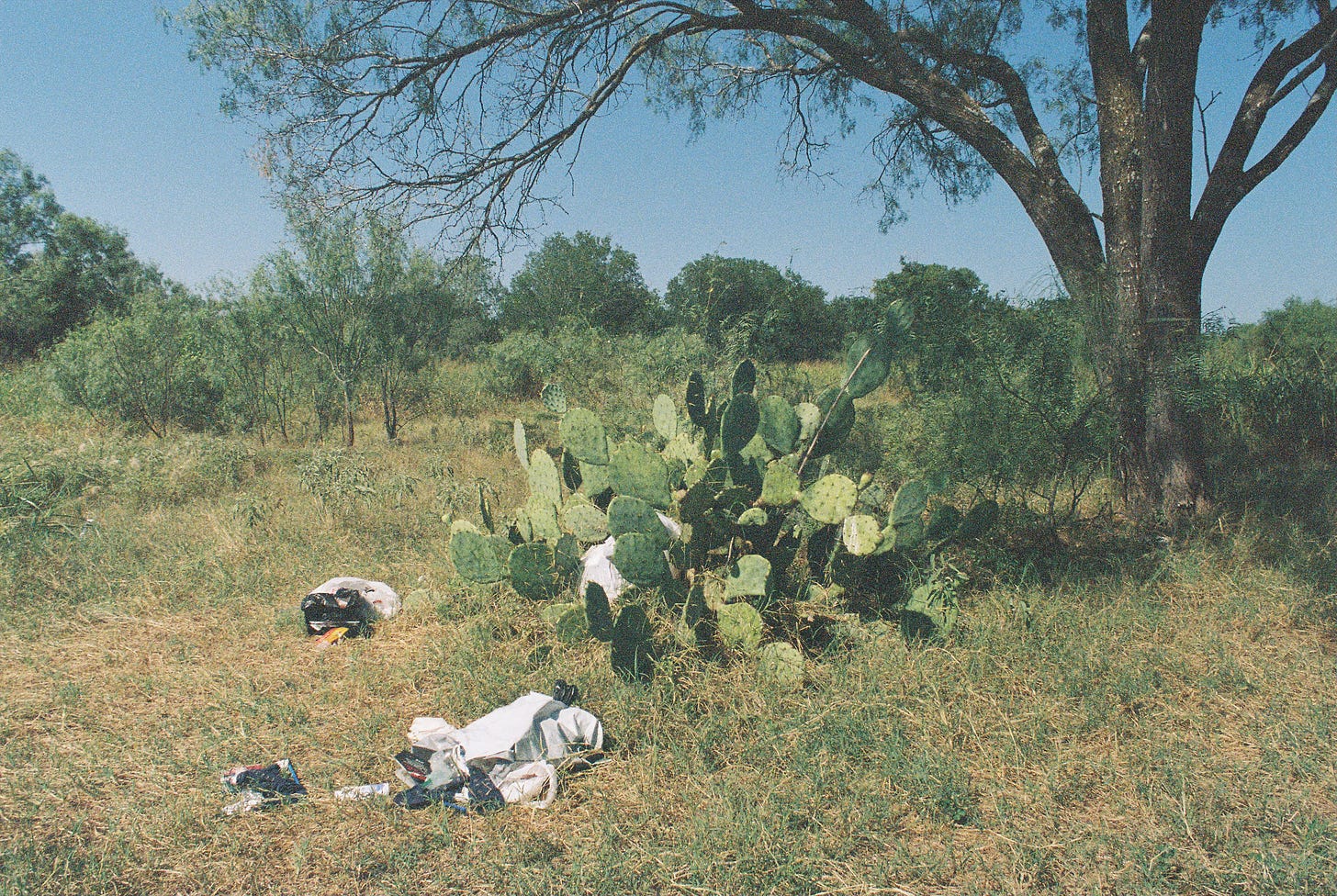

I walked home the way I came, through the woods and along the old right of way behind the dairy plant. It was a lot hotter on the return, and at one point after choosing a route I thought unlikely to disturb any more encampments, I realized I had managed to get myself deeply embedded in an extensive patch of cactus I thought I had evaded only to find a big spine sticking out of my leg. There were a mix of species, mostly prickly pear but also a prodigious new growth of the pencil cactus tasajillo, whose Christmas bulbs had not yet reddened.

When I got through, I found myself at the edge of a construction staging area that had just been laid out along the road, where an old potable water line under the river is about to be relaid. They had bulldozed some small trees out of their way, and the remains of some camps. In the clearing I found a legless gamer chair, some cool drawings laminated for protection, and a big pile of CDs.

I recognized one CD immediately, because it was one I used to have. Emperor Tomato Ketchup by Stereolab, which I remembered as one of my favorite records of the late 90s, and hadn’t listened to since the late 90s.

I took it home, cleaned it, and it played. But the feelings of that world it came from, the optimistic moment between the End of History and the beginning of the long dark that was uncorked on 9/11, when the World Wide Web was the new new thing and the promise of the century to come was foretold with utopian certainty, were like they had been translated into some language I no longer knew.

“What’s society built on?” the French girl sang over and over, acting like she knew the answers.

The Roundup

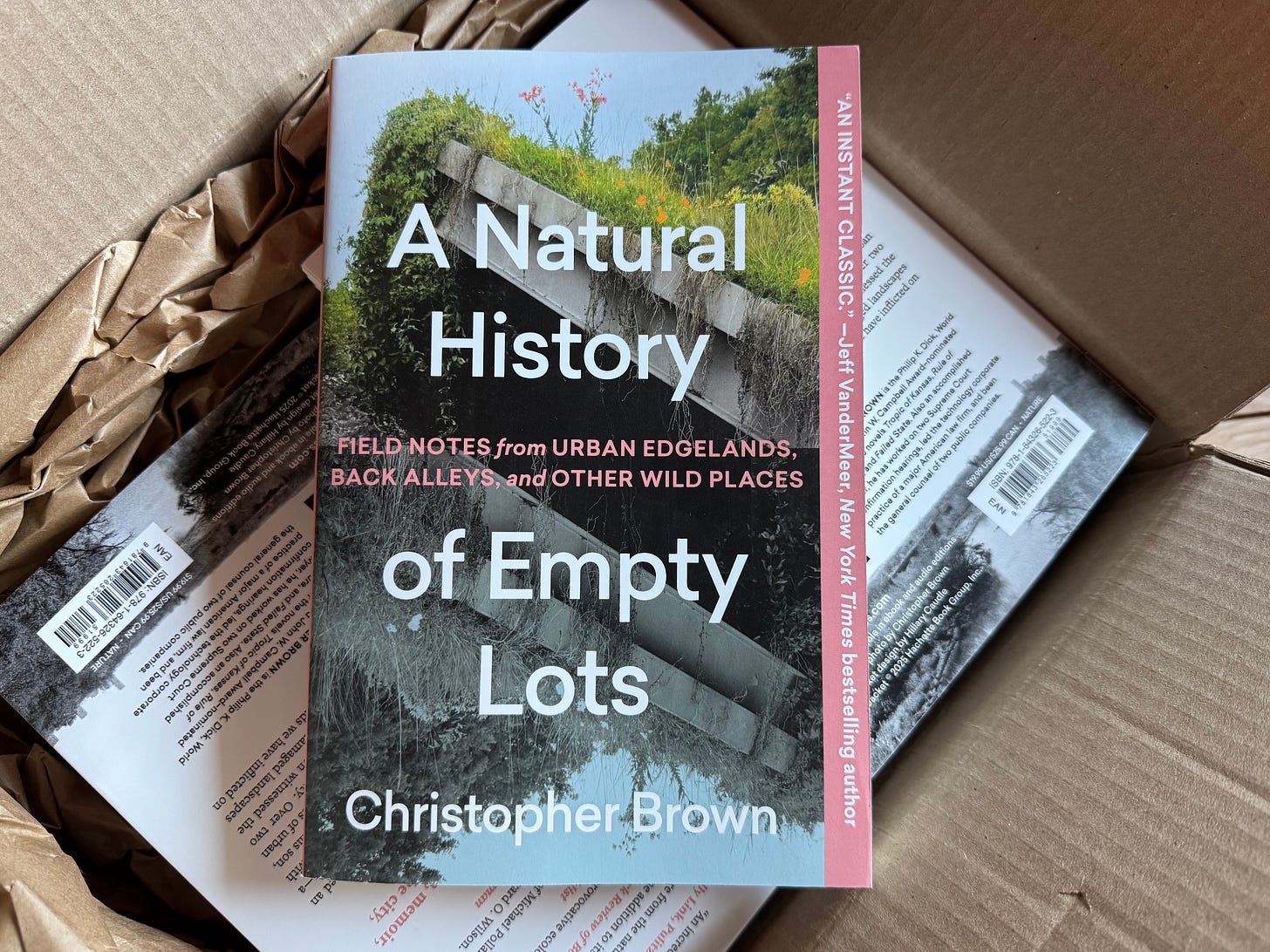

If you’re in the Austin area, please join me October 7 at Alienated Majesty Books on 29th St. for the launch of the paperback edition of A Natural History of Empty Lots. We’ll be screening Brett Gaylor’s short film Field Notes from an Apocalypse, which documents some walks in urban woods and a paddle to the Tesla Giga Texas factory, and then climate activist Alexia LeClercq of Start:Empowerment + PODER, anthropologist Craig Campbell of UT-Austin + the Bureau for Experimental Ethnography and I (and potentially one other panelist) will be in conversation about how to find (or fight) our way to a better future from here. RSVP and details here. And if you haven’t checked out the book but are interested, you can preorder the paperback (or order the already-available hardcover, e-book or audiobook edition) here.

On November 5, I’ll be teaching a single-session class “Writing the Natural World: A 21st Century Reboot” for the Writer’s League of Texas, online from 6:30-9:30 pm CST. Details and registration here.

I have several other local and regional events and some new short-form publications scheduled for the coming months, so watch this space for details and links as they become available.

Speaking of preorders, Makenna Goodman’s brilliant new novel Helen of Nowhere will be published on Tuesday (Sep. 9) by Coffee House Press in the US, with a UK edition to follow from Fitzcarraldo in January. Told in four parts, short enough to read in a single sitting, with the same razor-sharp language and voice that made her first novel The Shame so hard-hitting, Helen of Nowhere tells the story of a house outside the city and a handful of people connected to it, and encodes in that story a deeper exploration that I think readers of this newsletter will connect with. I’m excited to see this book getting the reception it and its author deserve.

(Full disclosure: Makenna was (is) my editor at Timber Press for Empty Lots, having taken on the project after the editor who acquired the book left following a merger. The book and I owe a tremendous deal to her.)

You also should keep your eye out for my friend Cory Doctorow’s new nonfiction book Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What To Do About It, also forthcoming on October 7 in the US from MCD and in the UK on October 14 from Verso. The book is technology criticism at its heart, a radical (and funny) political economy of early 21st century capitalism (it’s even been shortlisted for the FT Business Book of the Year), and its explorations are also relevant to how we think about our ecological and climate trajectories.

From cooler climes, here’s a cool new urban nature newsletter from the NYC Plover Project.

Last Sunday I harvested my first batch of chiltepin for our table, from this lush bunch of ur-peppers I found growing amid the concrete rubble dumped at the back of our lot before we got here. If you live in a region where it grows, it’s a really fun forage and an easy one to make into a delicious hot vinegar or salsa.

Enjoy the full moon, and have a great week.

Great post, and a great music rec! I’ve been on a Telepopmusik kick, which has a similar optimism, before the “uncorking of the long dark”, as you put it so well. Thanks!

I had never heard of a cicada killer before, and since here in Australia we have lots of cicadas, I did a little research and found we do have one. It is a different species; Exeirus lateritius, the sole member of the genus Exeirus, is a large, solitary, ground-dwelling, predatory wasp. It is related to the more common genus of cicada killers, Sphecius. In Australia, E. lateritius hunts over 200 species of cicada and acts in the same manner that you describe in your Field Notes. I look forward to your newsletter. All the best