A Walk to the Lost World

No. 165

Wednesday morning, feeling the call of the cool air and the late sunrise, I took our old dog for a walk in the woods behind our house. We’ve been so busy this autumn that I haven’t had as much time for such excursions, and over the summer Lupe had been showing her age at 14 years, not interested in much more than limping halfway down the block and back. The fall has rejuvenated her, and she was ready for the kind of ramble we have been doing since we adopted her in the summer of 2010, when she and her sister were living as abandoned pups on the couch behind the diner, weirdly native to this place we found.

I let her pick the route, and she led me down the bluff, past the spot where the cottonwoods grow super tall at the mouth of the big drainage pipe that channels runoff from the nearby streets, and on to the rock beach, an old gravel dredging site that has gotten thicker with vegetation every year we’ve been here, the waterline almost inaccessible now through the thick clumps of switchgrass. A few late bloomers were still flowering, including the last purple of the salvia, and tons of the red-whiskered white clammyweed coming up in the river rock.

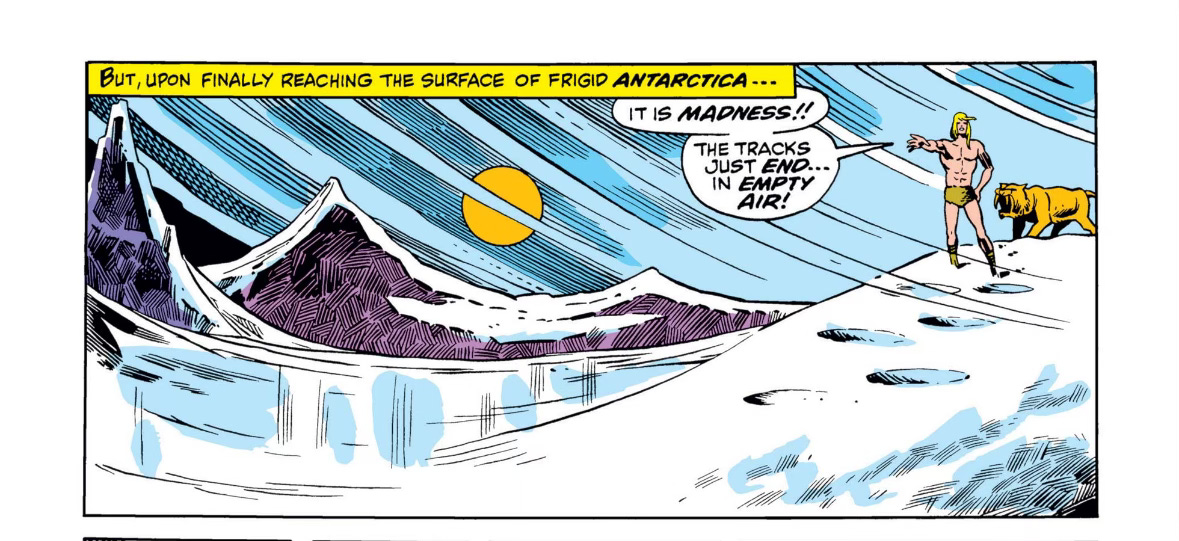

I had been reading the news reports about the greening of Antarctica—a sudden increase in moss establishing itself on a rocky island near the Antarctic Peninsula, which over time may lead to the accumulation of soil in which rooting plants can establish. One of those everyday climate change shockers that tells a more complicated story than the headline writers think. Then on Tuesday, my silly Marvel Comics tear-off daily desk calendar, picked up two months into the year for a dollar at the used bookstore next to our daughter’s swim school, had another image of green Antarctica: the cover of Hulk #109 from 1968, in which Hulk visits the Savage Land.

I grew up reading such stories. The Savage Land, an antediluvian wildlife sanctuary hidden by aliens underneath Antarctica, was a late addition to the rich pulp literature of lost worlds and hidden valleys. The trope first appeared in the Victorian era, with H. Rider Haggard’s lost African cities, Jules Verne’s secret world in the center of the Earth, Arthur Conan Doyle’s Amazonian plateau and Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Antarctic island where dinosaurs still roam. Fantasies of escape from the cartological enclosure of terrestrial reality that emerged when human dominion over the planet had been perfected at the end of the imperial era.

I had never really considered the way such stories consistently embed within them Edenic visions of wild green nature uninfluenced by us. Often in Antarctica, no doubt because that was the last place on the planet we had not yet fully occupied and explored. That got me thinking how my lifetime of walks outdoors, sometimes in wilderness areas at the continental extremes, but more often in urban woods and riparian areas, were about a similar search for smaller and realer pockets of wild life in the margins we’ve left.

In A Natural History of Empty Lots I have a chapter about the discovery, not long after I bought this brownfield dumpsite where we made our home, of a hidden wetland down behind the dairy plant nearby, in the middle of which sat an old Chevy that had acquired the totemic qualities of one of those architectural relics of a vanished civilization. A place I was sure, when I first stepped through the trees and gazed upon it in the spring of 2009, was some intact remnant of what the Colorado River corridor had been like before human settlement—only to learn over the years that it was a spot where heavy industrial operations had been conducted as recently as the 1970s. Once those operations ceased, nature quickly and dramatically reclaimed the zone, which was inadvertently protected by the fences and roadways of the industrial corridor that surrounded it.

The Impala disappeared more than a decade ago, but we still like to go find that site, which is different every time you visit it. When we first encountered it, the plants seemed to be almost entirely native, a biodiverse array of water grasses that had adapted to the weird way the river below the dam would undergo frequent and dramatic shifts in water levels, ensuring a steadier flow than the gnarly creek that fed the wetland with urban runoff at the other end. The winter storm of 2021 seemed to have killed off a lot of those aquatic natives, creating an opportunity for the elephant ear to move in.

That’s what Lupe and I found on Wednesday as we walked back to one of the entry points—a thick growth of Taro, Colocasia esculenta, a native to tropical regions of other continents that thrives in our riparian zones, including in shady spots. This summer, after some initial incursions over the past couple of years, it has totally overtaken a swath of seasonal wetland that four years ago had been dominated by native grasses, and a place where we would often encounter strange native flowers we had never seen elsewhere. This may be the densest patch of elephant ear I’ve ever seen. It looked impassable and daunting, physically and emotionally, the way a well-established patch of Johnson grass does when you find it on higher ground.

We walked on, following the edge along the high bank. Lupe checked out the old armadillo den we found many years earlier, where the rootbed of a big hackberry is partly exposed at the point where the creek that originates in the drainage ditch behind the door factory empties into the wetland. And there, you could see the elephant ear had not had as much luck in the sunny part of the wetland.

Turns out elephant ear was introduced to the U.S. in 1910, originally as an alternative crop to potatoes, only later as a popular ornamental. It’s a tuber, and a staple food in some regions where it is native, from Africa to Asia. In Vietnam they call it khoai môn, and make a variety of tasty curries with the corms. Even the leaves and stems are edible. It made me wonder if we should try to harvest some from the secret swamp, and check out a few of the recipes. And it got me thinking that our little lost world below the overpass told a more complicated story about the ecological changes happening around us than my reflexive natives versus invasives narrative.

Perhaps our great-grandchildren who survive the crises that are coming will find the Taro growing wild across this overheated and drought-ridden region as an abundant natural food source. Or maybe they will be long gone from here, relocated to the newly green islands along the coasts of Antarctica, seeing if they can do a better job taking care of the world they inherited than we did. With luck those daydreams of the dystopian novelist will prove to be no more than that, as we figure out a way to live in better balance with the next nature that is aborning all around us, popping up through our footprints on the Earth.

The Roundup

My local comic book store said they had a copy of Hulk 109 when I called, but it was $100, so I got myself a trial subscription to Marvel Unlimited and read it on my phone. Old comics are not the same without the printed color, the ads, and the feel of the physical object, but it was entertaining to see how free-form the story was, with Hulk as the ultimate wanderer who jumps from place to place every issue. In the beginning of issue 109 he is in China, smashing up a military base. He gets to the Savage Land when he jumps on an intercontinental ballistic missile that his weight drives off course. There, he and Ka-Zar learn that a mysterious device left behind by the aliens has turned on and is about to transform the climate of Earth to make it more habitable for the spacefaring extraterrestrials when they return. They didn’t know we would do that for them.

For more on the greening of Antarctica, see this piece from the Oct. 4 issue of Nature.

For more on lost world stories, you can start with this entry at John Clute’s online Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, or the Wikipedia page on the topic.

Friday was the 50th anniversary of Tobe Hooper’s Austin grindhouse classic The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, a movie I remember being in the theaters when I was a kid, but only had the nerve to watch for the first time when I was more than 50 years old myself, researching eco-horror, and finding myself fascinated by the depictions of nature embedded in the movie, all of which was shot around here. Friday I got to experience the feeling of seeing Leatherface on my lunch break, when I walked down to City Hall to check out the restored Ford Econoline van they hauled out for the commemorative ceremony.

Monday’s NYT had a great piece about the restored prairie strips of Iowa, encouraged by the development of a new CRP program that subsidizes such projects.

Thanks to Jesse Sublett for tipping me off to this cool piece from Wednesday’s NYT about the wild ravines of Toronto.

And it was thanks to Robert Macfarlane’s posts on the subject that I learned of the legal proceedings pending in Britain that test the bounds of the right to roam, in a case brought by the owner of an estate in Dartmoor trying to prevent hikers from camping or even picnicking on his land. See Tuesday’s recap in The Guardian for more. I’ll be curious to see what the court rules, and it makes me wonder if we might yet find similar doctrines deep in the roots of the common law we inherited from the English.

Book News

Daisy Alioto’s fun interview with me about Empty Lots is now up at Dirt, and my wonderful conversation with Lisa Smith and Margot Carrera at Big Blend Radio’s Nature Connection podcast is now up on their site.

Thanks to Fred Nadis for tipping me off that Carolyn Kellogg’s wonderful L.A. Times review of Empty Lots ran in Sunday’s print edition (and for sending me the clip that arrived in Friday’s mail).

This Wednesday evening I’ll be back in Des Moines for an event at Beaverdale Books. Hope to see some Iowa readers there!

In November, I’ll be at the Texas Book Festival in Austin Nov. 15-17, then in Seattle at Elliott Bay on Nov. 21, and at Powell’s in Portland (where Empty Lots is a Powell’s Pick) on Nov. 22.

And I’m delighted to report that, by popular demand, A Natural History of Empty Lots will be officially available in the UK and Australia. The date for the Hachette UK release is January 9; Australia to follow.

Have a wild week.

One minor caveat to harvesting that elephant ear: get it tested for heavy metals and other industrial byproducts first. Marsh plants in general are great for “polishing” water by trapping all sorts if pollutants, to the point where they’re dangerous to eat or even to use as compost. Myself, I’m incredibly fond of so-called Cossack asparagus, the immature leaves at the base of cattail stalks, and cattails have so many edible components at various stages of growth that Euell Gibbons referred to them as “the supermarket of the swamps.” Problem is, most of the best growing spaces for them in my my immediate area of North Texas are nearly saturated with lead, cadmium, and other heavy metals, and I’m seriously concerned about levels of PCBs (Dallas had several factories dedicated to electrical equipment manufacturing that just dumped PCBs into the Trinity River) and random bits of illegally dumped industrial waste. If it turns out yours are metal-free, though, bon appetit.

Really beautiful. So glad Lupe took charge again. Wasn't expecting The Hulk, a fascinating layer.