A natural history of the supply chain

If you look this parcel up on the county assessor’s site, you’ll see that the subdivision is named after Lockheed, a reminder that the nearby airport was once an Air Force base and this whole zone dominated by businesses that served it from World War Two until the end of the Cold War. Right in the middle of it on the online maps someone has marked the location of the Ramp of Mystery, an enigmatic ruin of that era that became a popular destination for urban motocrossers. And when you walk the lot in the quiet of first light and see the concrete pictograms carved into the plain, it’s easy to wonder what the whole story was.

A couple of months ago a supply chain bot dispatched me to an address in Southeast Austin, on a street that sounds like it was named by a corporation, in a neighborhood of windowless big box buildings behind tall iron fences. My destination was a new Amazon logistics hub, and when I went there to return an object I no longer remember, navigating the parking lot Pac-Man of Prime trucks and one-way lanes, I noticed the woods behind the building, and thought it would be an interesting place to explore. Thanksgiving morning, in the calm before the insanity of online Christmas shopping, seemed like the perfect time.

I wore a tweed jacket for this particular bit of early morning trespassing, made sure I had a few “Attorney at Law” business cards in my pocket, and thought about what my story would be if I ran into any security guys. I headed out right at daybreak, with the dogs. The site is almost directly south of our home, maybe two miles as the crow flies. It was an overcast morning, with dim light, and as I hoped there was only a skeleton crew in evidence at Amazon—just three or four cars in the lot, one semi unloading at an open dock way in the back, and empty Prime trucks lined up like planes on the deck of an aircraft carrier, resting up before Black Friday and the season of maximum consumerism.

In the two months since my first drive-by, much of the green space I had seen had already been razed. Behind the data center next door they were prepping the site for another big white box, replacing the dirt with a thick ballast better able to support the weight of what was to come. But the woods were still there beyond the open field, and the construction workers all had the day off, so I parked my truck in the Amazon lot and walked on back like I knew where I was going.

The outer perimeter of the new building pad was demarcated with silt fences, right up against a row of fresh survey markers and a very old and slack barbed wire fence. We stepped over those and followed the closest thing we could find to a path, probably an overgrown remnant of a dirt road.

I had done a little research before coming out, and learned that this site was one I’ve had on my list for a while, after Omar Gallaga had written it up for the Statesman two years ago, trying to unpack the enigma of the “Ramp of Mystery,” an unexplained wonder at the edge of town that had acquired a certain legend.

Turns out this was the test site of an early experimental drone, the Lockheed MQM-105 Aquila, a catapult-launched remotely piloted vehicle designed for target designation. The site was active in the 80s, until Lockheed lost the contract. There’s a pretty informative Reddit thread about it, with one ex-employee gratuitously noting that the site was also next to one of the last of Austin’s drive-in theaters and “you could watch X-rated movies from some of the taller ramps.”

I waited too long to check it out. The ramp is gone now, a Cold War relic razed to make room for more data farms. I suppose it’s possible I missed it, like one of those explorers who doesn't notice the pre-Columbian pyramid underneath the foliage right in front of their face. I did find other structures that were probably part of the Lockheed facility—wood frame sheds collapsing under corrugated metal roofs, Johnson grass growing up between the fallen boards.

I didn’t see much sign of wildlife, though the dogs were pretty amped up at the scents on the ground. Mostly what I found back there was a cactus garden, where the old launch ramps and parking lots have been overtaken with diverse species of spiny plants. A remarkable number of pencil cactuses, big paddles of prickly pear, and large quantities of seasonally-appropriate tasajillo, the red-fruited cholla sometimes called Christmas cactus, which the foragers say makes good eating, if you can figure out how to handle it.

The site stretched back a decent ways to another section of even older fence, where you could see the land dropped down into a deep creekbed, one whose course I later realized the nearby roads follow, and whose deer trails likely lead to the backside of the airport motels and trailer home assembly yard on the frontage road to the north. But we stopped there, and continued our search for the ramp, bushwhacking through the cactus garden against the ambient background track of a half-dozen cooling fans humming above the data center. We saw a television antenna above the trees, and then a billboard, just far enough away that you couldn’t read what it said.

We found one shed that was still standing on four pillars, enough to have provided shelter not long ago to one or more people who were living back in there and left a massive quantity of found objects behind when they cleared out. Electronic devices long unplugged, overturned mattresses, a stuffed bear passed out in the field, a VHS tape of Yankee Doodle Dandy, and a figurine of pigs with apples that I regret not taking as a souvenir.

Before we left, I took the dogs to check out another empty field—the one on the opposite side of the street from the big boxes, which I had only noticed when we drove up there that morning. A few acres of short grass dotted with trees. Public property, from the looks of it, with signs of waterworks and a frisbee golf course back in there at the edge of a residential subdivision. Behind the trees to the southwest stood a big modernist office building that looked the matte background of some 70s sci-fi dystopia. But what really got my attention were the trees.

They dotted the entire expanse of the field, with savanna spacing, each one with the dimensions of a live oak—low, thick, and sprawling. But they weren’t oaks. They looked more like mesquites. When I went up to investigate one, I realized it grew from multiple trunks, almost as if it were several trees growing together in a group. Huisache, the sweet acacia, a tree named by the Aztecs for its spiny branches that sports the most gorgeous golden yellow blossoms for a short burst in early spring and whose bark is said to make a potent hallucinogen. We have several huisaches in our yard, recently pruned to go vertical, even as I now see that’s not the way they are really meant to grow, in their adaptation to this climate where cacti thrive, maybe more so now than used to be the case.

As I stood there admiring these amazing trees that must have been there long before the city came to surround them with logistics hubs and data centers and drone pads, I saw a flock of birds flying over the Amazon facility in a rough V-formation, headed south-southwest. Terns, from the look of them, maybe coming from the same zone as the Alaska Airlines 737 that also showed up in the photos. Rather far inland, if my guess is right, but I was happy to see them and the ancient trees there in a place that reminded me how good we are at erasing the wild, even when we name our companies after it.

Black Friday mail call

One of the ball caps I wear on my walks features a patch my son sent me from Korea advertising, in koanic Kringlish, “FREE CATALOG.” I’m not sure why he and I both think that’s funny, and no one ever seems to remark on it, but I like it, especially because it also reminds me of him, separated as we are by an ocean and a quarantine that makes international travel almost impossible.

This is the season when the free catalogs arrive in bunches, stuffing the mailbox every day. Most of the catalogs we get targeted with now are for food and kid stuff, but I still get a good number for outdoor gear. I have long been fascinated by the stories these catalogs tell, and the lying mirrors they present, more than a few of which have successfully rooted in my brain over the years.

The outdoor catalogs are interesting in the way they sell city-bound people on the dream of getting outside as something that requires special gear only they can provide. It’s a very American thing, rooted in the way much of our consumer culture originated with frontier outfitters who would supply people with the things they needed to migrate across a continent or go look for precious metals buried in the earth of California or Alaska, and who spawned Sears and the other mail order catalogs that supplied the settlers of this colonized space with the things they needed to replicate civilization on prairies that had just gone under the plow, like the farms and ranches that used to be where that Amazon hub is now.

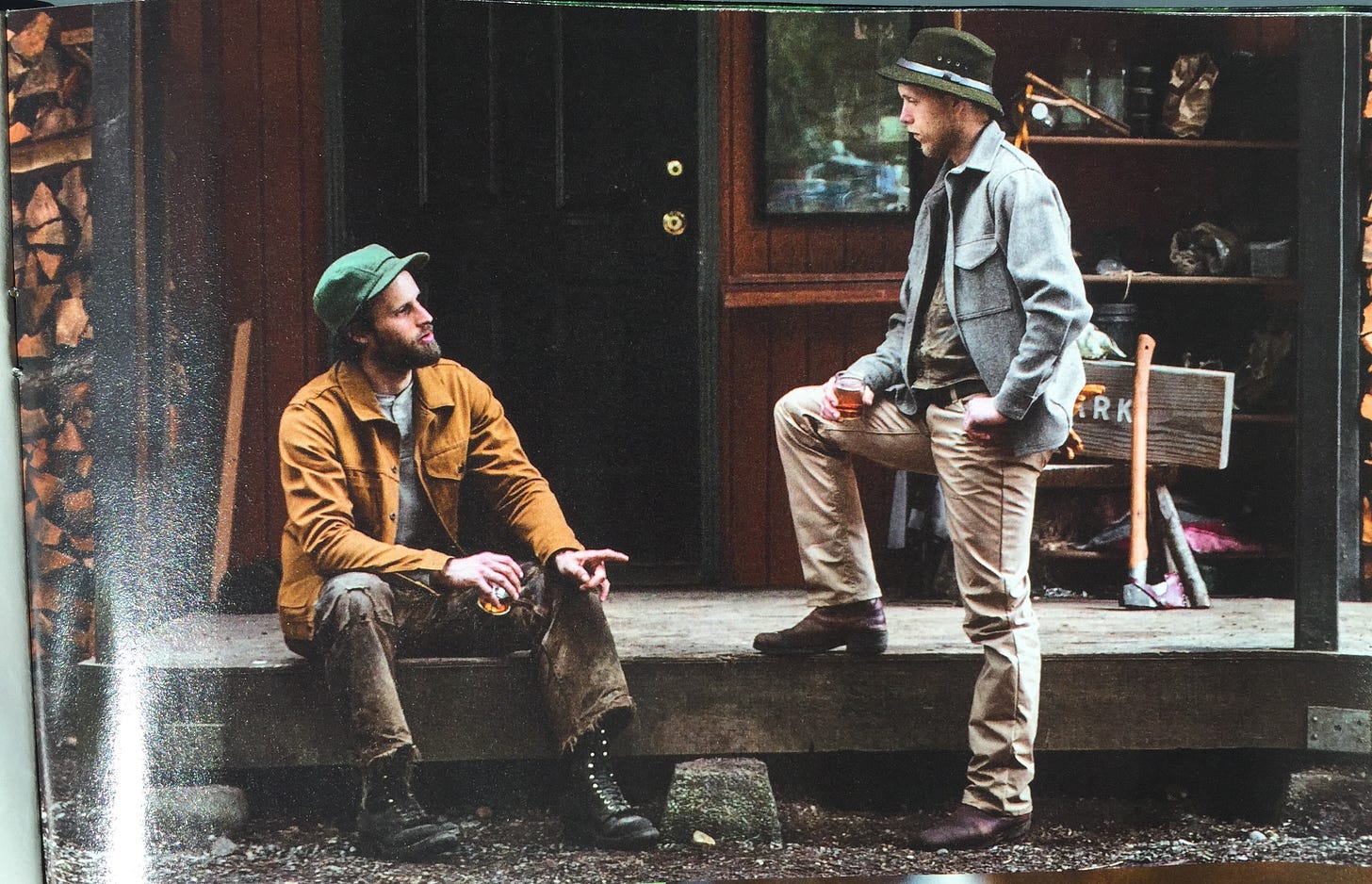

Some of the most unintentionally entertaining of these catalogs come from Filson, a Seattle company whose roots really are as an Alaska outfitter. I am a sucker for retro gear, and I have bought some stuff from them over the years, including a pair of waxed overalls that seemed like a good idea for heavy backyard rewilding, only to quickly acquire the kind of odor I should have thought to expect from an unwashable moisture-sealed full-body garment deployed under the Texas sun. Filson kind of jumped the shark when it got cross-pollinated with the hipster search for pre-digital authenticity, and the catalogs often broke through the wall of self-parody.

When I was a kid, many of the catalogs that arrived at our house targeting my dad didn’t even have photos—just drawings of the items, accompanied by dry factual descriptions. J. Peterman was one of the first that really grabbed onto the idea of catalog copy as adventure story, each entry a condensed Merchant-Ivory screen treatment, fully embracing the possibilities of a photo-free advertising medium that doesn’t even show you what the products really look like. The catalogs that show up in our mail now treat every photo as cinema, with narrative expressions so over-the-top that they read like German Romantic paintings imagined by Capital’s inner art director, selling a fantasy of life outside and access to a wild frontier that is as absolutely gone as the drone ramp I went looking for Thursday.

I think peak Filson was this guy who showed up in our mailbox last year, realizing the post-apocalyptic possibilities lurking in the negative space of a forgotten Gordon Lightfoot song:

Most of my outdoor clothing is as permanently dirty as this guy’s, from actual use, as even a mall-trained consumer like me eventually realizes that’s how outdoor gear is meant to be, after years of daily outings into the pockets of nature you can find behind logistics hubs and dairy plants. And the stuff that holds up the best for me comes from another Pacific coast company whose catalogs also sell a vision of life outside in faraway places that sometimes looks like the storyboards of a cli-fi catastrophe, but at least the Patagonia photographers take it in a more utopian direction, as in this memorable outtake from last summer:

I’ve been reading from a few classical and anthropological works about ritual sacrifice lately, thinking about the connections between nature and the kinds of stories we call horror, and the way most of our religious traditions are rooted in agricultural practice and our effort to control nature. One of the best modern studies of such practices is Frazer’s The Golden Bough, with its epic survey that starts in the sacred grove of Diana Nemorensis and ends by cracking the code of the death of Balder and what’s really up with all that mistletoe. I more recently discovered The White Goddess by Robert Graves, which kind of takes The Golden Bough and runs with it in the way only a poet can.

Thinking about gear catalogs, and about the financial stresses American families endure each year as soon as the Thanksgiving leftovers go to the fridge, and about what’s really going in that Amazon facility, I wonder if our consumerist Christmas is a kind of ritual sacrifice, in which we burn up a healthy chunk of our year’s labor, more out of a sense of duty than fellowship, to feed the bizarre economic system we built from the self-adoration our agricultural civilization endows. It’s a half-baked idea, but a lot of the elements are there, and it makes me wonder what better winter solstice ritual we might replace it with, in this weird year that gives us unexpected windows into how else it could be.

Have a great week.

What a great discovery your writing is.Thank ye.

Another wonderful blog to launch my week on a thoughtful and erudite path. I look forward to reading your weekly blog. Thanks. WB