A Memorandum from the Department of Dead Animal Collection

Saturday morning the dogs killed an opossum in the yard. I had let them out when I woke around 4, into the dark of the new moon, and knew something was up when I called them an hour later and one of them wouldn’t eat and the other wouldn’t even come. I only discovered the carcass when I stepped on it in the dark, with sandaled feet. They had left it right in the middle of the driveway. The opossums usually enter from the street, like the cats who come to steal the wild birds. The foxes, armadillos and snakes are the ones who sneak in from the forest behind the factories.

Disposition of dead animals from one’s yard is a dark art. It happens often enough here that I have a shovel just for that purpose, one I usually keep propped at the back gate in a way designed to block a gap in the fence and impede future incidents. I use the shovel to return the animals to the woods, and let nature do the rest.

If you spend much time in these woods, you come across a lot of dead animals. Especially in winter, when the coyotes seem more active, and you may step into a clearing to find the remains of a deer they have taken down. The river is wild kingdom all day long, never-ending smorgasbord of the herons who strut around in the shallows like predatory supermodels at a grisly live sushi bar. In the early morning the caracara come out to find whatever carcasses have been left on the banks by the night hunters. Nature is Metal, as the dark Instagrammer proclaims, in a gruesome feed that proves its point aggregating footage of animals and their kill from around the world. Here’s one of the tamer posts:

But as intense as the struggle between predator and prey may be in the urban wild, in the city you’ll always see more death at the side of the road. The City even has a special team for just that purpose: the Department of Dead Animal Collection. You can read their call log here: 29,850 3-1-1 requests in the last two months for someone to take the thing away, each entry encoding a micro-horror in the weird machine prose of emergency dispatchers:

box wrapped with a black bag , a rabbit, in front of building 5

Or this one from the frontage road:

Deceased female tabby cat no chip, no tipped ear. Hit by car. Placed in white plastic trash bag with pink note at the maintenance road to the retention pond past car dealership, before Pond Springs. See alfp

The city is a dangerous habitat. But it’s also a rich one full of easy food, especially for rodent hunters, like the red foxes that live around the culvert behind the door factory and often sneak out under the gate at night to prowl the concrete jungle. It’s a crazy thing to see them trotting through the beam of a streetlamp, headed home after a successful hunt on the other side of the highway.

As gruesome as roadkill can be, the worst animal death to witness in the city is the kind caused by our trash. I learned that lesson six years ago this winter, walking the dogs down in the floodplain, in a scene I wrote about for a special nature-themed issue of my friends’ litzine:

I can’t follow a scent as well as my dogs. Especially not the smell of rotting mammal I picked up the first morning of December, which was more like a cloud. A warning. I wonder if it was against nature the way I instinctively wanted to check it out. It came from a place that didn’t want me to enter—a patch of dense, weedy woods between the river and the big wetland where the herons like to hang out and watch the planes come in. But I found a way to crawl through the lattice of ragweed, vine and scrub, dragging my reluctant dogs with improvised simian yoga, following my own loco nose to a scene I was not meant to see.

When I saw it an actual frisson of real, deep fear ran through me, almost before I made sense of the distorted shapes. Which part was branch, which part bone, which part body?

The clear plastic coated the tangle of wire that gigged the deer. It was a horror show torture scene, the way its big long neck was stretched out in the V of the trees, pulled taut by the cable that tied its rack to the branches. The front legs hung, barely touching the ground, while the hindquarters were starting to dissolve into the shadowed ground. I thought a human must have done this—strung the animal up for cleaning. Then I came around the other side and figured the deer must have gotten itself caught in a tangle of human trash, something the floodplain is full of. No signs of wounds other than those left by the animal scavengers. A plausible path for a fast-moving deer. A pose that could reflect intense struggle, then exhausted resignation.

As I documented in the piece, I became briefly obsessed with the mystery of this unexpected crime scene, and with the indignity of what had happened to this beautiful animal. I told the story to a friend over lunch that day, of my inability to tell whether it was accident or atrocity or both. He told me of dark human mischief other friends had witnessed in those same woods. I called the authorities—the animal cops. They assured me the deer probably just got its rack stuck in the wire, then got caught up in the vines, something that happens often.

“Dead animal collection won’t go out for something like that,” said the dispatcher, but it wasn’t until we were off the phone that I processed the fact that there was a municipal bureaucracy devoted to that task.

I ended up returning to the scene a few days later with wire cutters and a shovel, cutting free the tangles and laying the deer down to disappear into the leaf litter. I went back a third time, months later. I never really solved the mystery, other than to better appreciate the quantity of other life our cities and our machines and the things we leave behind destroy without even noticing.

For the full story, if you’re interested you can check out “Winter in the Feral City,” in Issue 33 of Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, published in 2015 by my friends Kelly Link and Gavin Grant, guest edited by ecopoet Michael J. DeLuca, and with nature-themed stories by many better writers than me including Carmen Maria Machado and Sofia Samatar. You can also get it from BookMoon, the Northampton bookstore Gavin and Kelly opened with Kelly’s MacArthur genius grant money just in time for the pandemic, and if you are looking for any other new reading, they are the best book recommenders I have ever had the good fortune to shop with.

News from the Insect Zoo

Monday afternoon I found this beautiful walking stick taking its siesta on our kitchen window. We get a lot of the chunkier Texas walking sticks hanging out in similar spots, usually on the steel of our door frames, which they seem to find safe redoubt for the prolonged copulation to which they are prone. These more classic Diapheromera are around, too, but rarely emerge from the foliage their bodies emulate so dramatically.

As I unsuccessfully tried to figure out which member of the Diapheromera family it was, here in the borderzone where many variants can be found, I became fascinated with just what a weird and wondrous creature it is, with antennae two-thirds the length of its body, forelegs that it rests against the antennae, perhaps as some additional camouflage, and a tail section that looks like a machine from some H.R. Giger fever dream:

When you find the detailed scientific explanations, you realize even the experts know very little about these aliens among us, even if they have an awesome vocabulary to describe the mysteries:

Common walkingsticks have very elongated bodies that are almost cylindrical. The abdomen and thorax are long and the abdomen bears a pair of single segmented cerci that resemble palps and serve as a clasper. The head is small but bears antennae that are about 2/3 the length of the body. Legs are slender and the tarsi are five segmented.

A distinguishing feature is the supra-anal plate, which is a small and membranous lobe above the anus. Their maxillae each contain a lacina with a tridentate structure. The species is apterous. Members of Diapheromera femorata exhibit square-shaped heads. Males are brown, whereas females have a hint of green to their brown color. There are other distinguishing characteristics that separate the two sexes; the femurs of males tend to be banded, their seventh abdominal segment is longer than their ninth, and they feature cerci that lack spines.

Courtship rituals seem to be absent for Diapheromera femorata. Exact mating systems are unknown for this species.

You can find the full entry on Diapheromera femorata here at Animal Diversity Web. With the full array of Diapheromeridae here at BugGuide.

And elsewhere in our feral house, here’s what I found Saturday afternoon when I went to grab my dirty sneakers:

RIP RBG

My friend Ed mentioned to me yesterday that the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was once a student of the novelist and master lepidopterist Vladimir Nabokov. I worked on Justice Ginsburg’s confirmation hearings as a young staff lawyer on the Senate Judiciary Committee, and if I had known that nugget of trivia I might have been able to write some better questions. We don’t tend to think of Justice Ginsburg in connection with the rights of non-humans, but reading about some of the recaps of her environmental cases this weekend, I was struck by a quote about how the green activism of youth gave her hope for the future.

Narrative Species

Week before last I had the opportunity to talk with the amazing Rick Kleffel for his long-running books program best known as The Agony Column. The show airs on NPR affiliates in Santa Cruz and the Monterey Bay, and this week the podcast version is up—episode 2092, to give you an idea of how long Rick has been at it. This was the third time I’ve gotten to speak with Rick, and it was a really fun conversation that included a lengthy discussion about nature writing and its connection with horror and speculative fiction.

Rick Kleffel on Failed State, at Narrative Species.

The Portal

Five years ago yesterday I came upon this remarkable work of earth art—a neo-Druidic portal where the trail disappears down in the hole behind the dairy factory, made from a broken hackberry tree and artfully threaded strands of the thick mustang vine that grows gothic in these woods. With some detective work I was able to find and connect with the otherwise anonymous artist, Cameron Krow. For more of his amazing work, you can check out his Instagram or this show at the Harwood Art Center, though the works are best experienced as the unexpected encounters with the wild uncanny they so wondrously reflect.

Opossum tongues

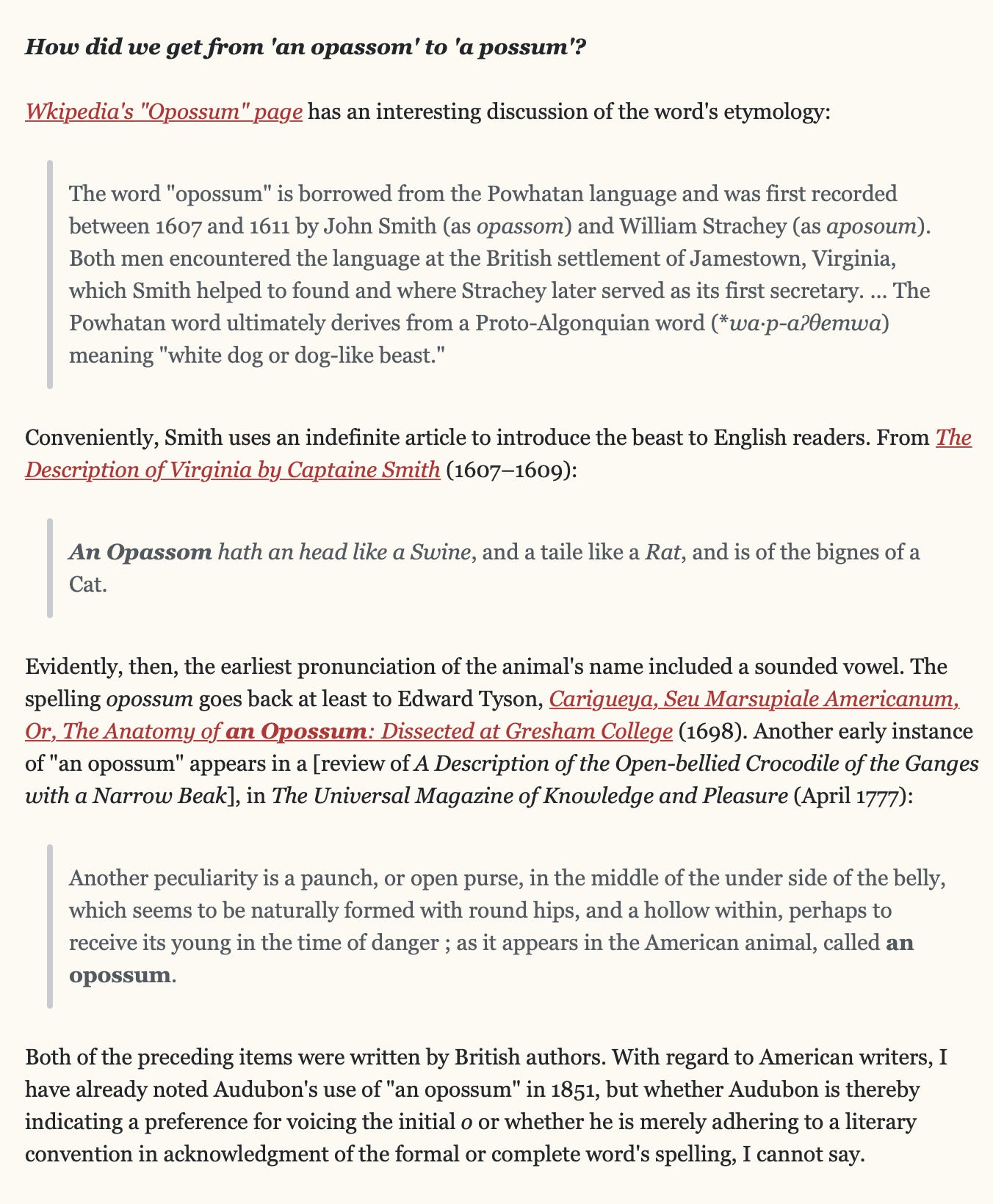

Writing this post, I disappeared into a different kind of portal, researching the correct article to use with the word “opossum,” which is generally pronounced in contemporary usage with a silent “o.” As expected, there is no definitive answer, but the entry on the subject at English Language Usage & Stack Exchange is a rich mix of etymological, natural and American colonial history (accompanied by troves of insane data, if you click through). Notably:

Have a great week, and enjoy the early autumn that seems to have arrived.